An Injection of “New Blood” Rejuvenates Older Rats

Researchers found that injecting blood plasma of young rats into older rats reverses signs of aging. The "new blood" improved organ function, along with learning and memory.

The transfer of young blood plasma to older rats can rejuvenate tissues and organs. Although it might sound like a sci-fi movie, a not-yet peer reviewed study, deposited online provided new evidence for this proposition. Transferring young blood plasma to older rats reduced markers of aging in their bodies, reversing the effect of aging by an average of 54% across body tissues.

The researchers conducting the study measured the age of mice via their DNA methylation patterns, in which chemicals called methyls are added and subtracted from our DNA over time. Methylation serves as a switch that turns gene activities on and off without modifying the DNA sequence. This process is known as epigenetics. Instead of measuring the age of mice in years, researchers can now measure the age by quantifying these patterns to determine the “epigenetic age” of the mice.

The epigenetic age which the team calculated can reflect how tissues and organs age, independent of their age in years, serving as a biological clock. Environmental influences and lifestyle choices such as smoking and overeating can make the clock tick faster.

To study the effects of young blood plasma treatments in older rats, the team evaluated and compared the epigenetic age of three groups: young rats, older rats, and older rats after treatment with young blood plasma.

Based on their data, the researchers observed reversals of epigenetic aging of 75% in the liver, 66% in blood, 57% in the heart, and 19% in the hypothalamus of the brain, giving an average rejuvenation of 54.2% across all four tissues. The brain stood out as not showing the same epigenetic age reversal as those of the other tissues.

Other scientists, such as David Sinclair, who studies the science of aging at Harvard University, suspect the blood-brain barrier may play a significant role in the brain not having the same epigenetic age reversal. The blood-brain barrier acts as its name implies, as a barrier. Some components of the new blood plasma, such as enzymes, antibodies, and other proteins can’t cross the barrier to enter the brain, which might explain the lack of age reversal effects in this organ.

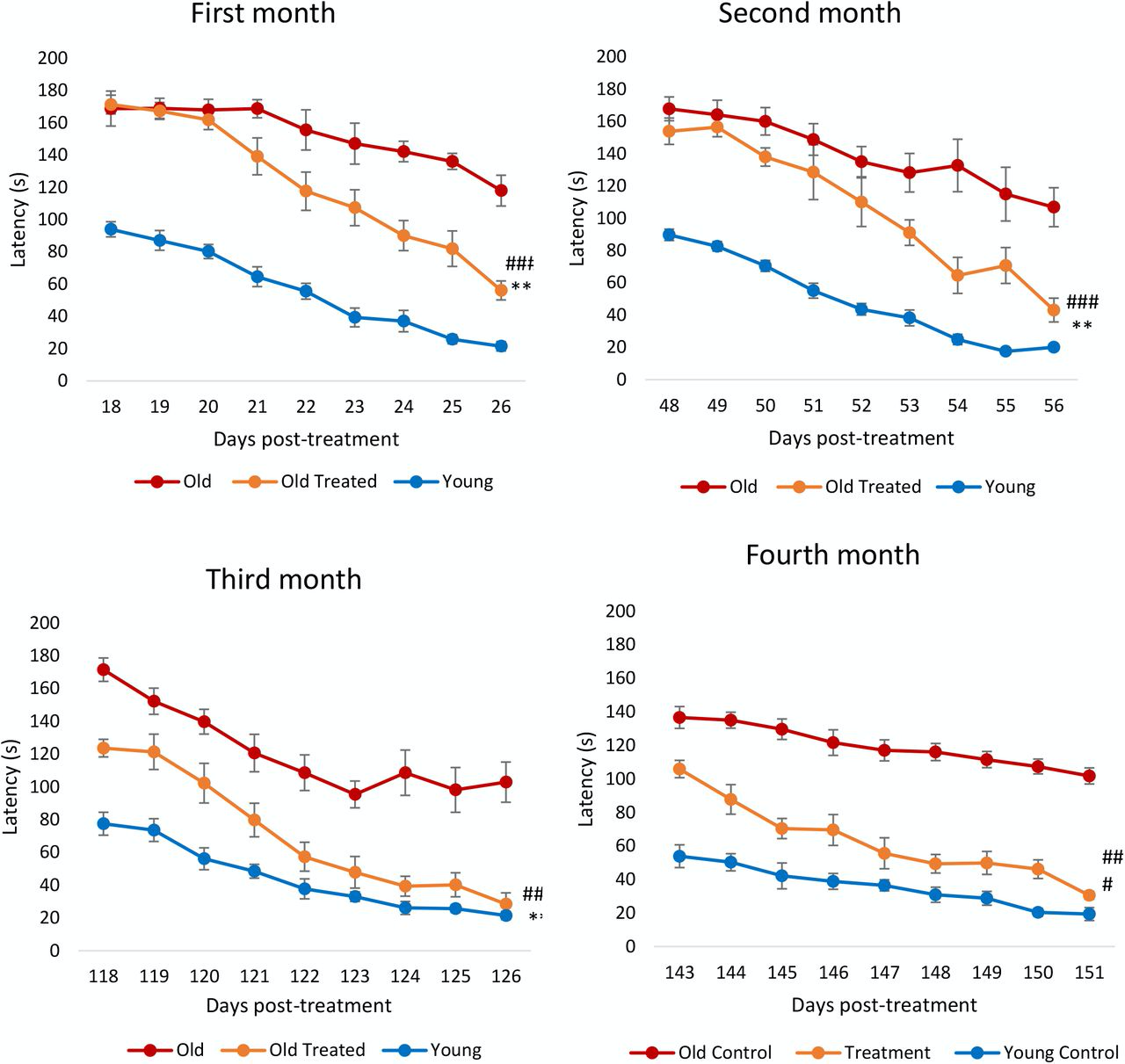

Importantly, biochemical measurements of organ function improved, along with behavioral responses used to assess cognitive function. After receiving blood plasma transfers, the older rats became faster at escaping mazes, a common lab test of cognitive skill. These reduced escape times, referred to as reduced latency, indicated improved abilities to learn and remember following young blood plasma transfers in older rats.

(Horvath et al., 2020) The latency period, which reflects the amount of time it took for the rats to escape from a maze, improved significantly for the older rats treated with young blood plasma. The red line in the graph indicates the latencies of the older rats, the orange line indicates the latencies of the older rats treated with young blood plasma, and the blue line represents the latencies of the young rats.

The question remains of whether these findings also apply to humans. In other words, could we store young blood plasma for future injections in our older years?

“Expect a rush to India to get this treatment. I do hope Nugenics [conducts] careful human clinical trials first,” said Sinclair in his tweet, referring to the Indian start-up providing this treatment. “In the US, young plasma treatments were stopped by the FDA until further notice citing a lack of proven safety.”

“If this finding holds up, rejuvenation of the body may become commonplace within our lifetimes, able to [systematically] reduce the risk of the onset of several diseases in the first place or provide resilience to a wide variety of infections,” Sinclair tweeted.