Calorie Restriction Preserves Brain White Matter by Slowing Cellular Aging: New Study Shows

A new primate study shows long-term calorie restriction preserves brain white matter by slowing age-related changes in oligodendrocytes and microglia.

Highlights

- Long-term calorie restriction dampens age-related gene activity changes in white matter cells – oligodendrocytes and microglia – of the aging primate brain.

- The intervention preserves myelin-related programs in oligodendrocytes, the cells that insulate nerve fibers.

- Calorie restriction reduces inflammatory and debris-related signals in microglia, the brain’s immune cells.

Aging is accompanied by a gradual breakdown of the brain’s white matter, the network of myelinated fibers that enables fast and efficient communication between brain regions. As white matter deteriorates, signal transmission slows, contributing to cognitive decline. This process is driven not by neuron loss, but by age-related dysfunction in supporting brain cells, particularly oligodendrocytes, which produce myelin, and microglia, which regulate immune activity and tissue cleanup.

Calorie restriction, defined as a sustained reduction in calorie intake without malnutrition, is one of the most robust interventions known to slow biological aging across species. While its effects on lifespan and metabolism have been studied extensively, far less is known about how calorie restriction influences aging in the primate brain, especially in white matter, which is highly vulnerable to age-related damage.

In a new study published in Aging Cell, Vitantonio and colleagues from Boston University and the National Institute on Aging examined whether long-term calorie restriction could blunt molecular aging in the oligodendrocytes of rhesus monkeys. Using RNA sequencing, the researchers show that lifelong calorie restriction preserves youthful gene activity patterns in oligodendrocytes and microglia, pointing to a protective effect on the brain’s structural wiring.

Calorie Restriction Preserves Oligodendrocyte Programs That Support Myelin

Oligodendrocytes are responsible for producing and maintaining myelin, the fatty insulation that wraps nerve fibers and enables rapid electrical signaling. With age, these cells accumulate metabolic stress and oxidative damage, reducing their ability to sustain healthy myelin.

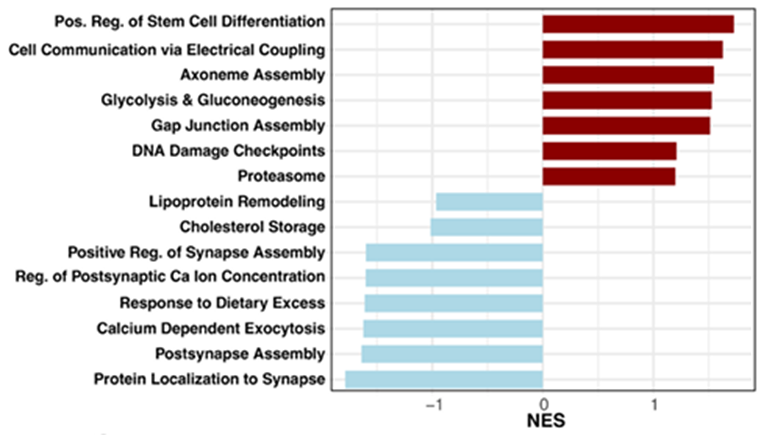

The researchers analyzed white matter from the anterior corpus callosum, a large bundle of nerve fibers that connects the brain’s two hemispheres, in aged male rhesus monkeys that had consumed a 30% calorie-restricted diet for over 20 years. Compared with age-matched controls, oligodendrocytes from calorie-restricted animals showed higher activity of genes involved in myelin production, lipid synthesis, and energy metabolism.

Notably, calorie restriction increased gene activity related to glycolysis and fatty acid biosynthesis, two pathways essential for generating the raw materials needed to build and repair myelin. A subset of oligodendrocytes also upregulated genes linked to cell adhesion and physical contact with axons, suggesting tighter coupling between nerve fibers and their insulating cells.

Together, these changes indicate that calorie restriction helps oligodendrocytes maintain a functional, myelin-supportive state well into old age.

Calorie Restriction Dampens Inflammatory Aging in Microglia

Microglia serve as the brain’s immune sentinels, clearing debris and coordinating inflammatory responses. During aging, microglia often shift toward a chronically activated state, releasing inflammatory signals and accumulating myelin debris, both of which contribute to white matter damage.

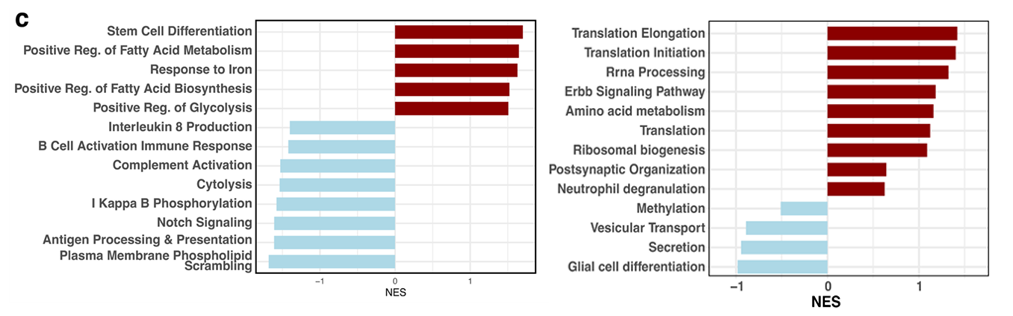

In calorie-restricted monkeys, microglia displayed a markedly different gene activity profile. The cells showed reduced expression of genes associated with inflammation and myelin debris processing, alongside increased activity of pathways involved in amino acid and peptide metabolism.

This pattern suggests a more efficient, less inflammatory microglial state, one better suited to maintaining tissue health rather than driving chronic immune stress. Importantly, these changes occurred without altering the overall number of microglia, indicating that calorie restriction reshapes microglial behavior rather than eliminating cells.

Calorie Restriction Alters Cellular Aging Without Changing Cell Composition

Despite clear molecular differences, the overall composition of white matter cell types remained unchanged between calorie-restricted and control animals. Oligodendrocytes, microglia, astrocytes, and precursor cells were present in similar proportions across groups.

This finding strengthens the study’s central conclusion: calorie restriction does not protect white matter by replacing cells, but by slowing the accumulation of age-related gene activity changes within existing cells. In other words, the intervention may preserve cellular function rather than altering brain structure.

Implications for Brain Aging and Cognitive Health

White matter integrity is a key determinant of cognitive performance in aging humans and nonhuman primates. Damage to myelin and supporting glial cells is closely linked to slowed processing speed, impaired attention, and executive dysfunction.

By preserving youthful gene activity in oligodendrocytes and microglia, calorie restriction may help maintain the cellular environment required for efficient neural communication. While this study did not directly measure cognitive outcomes, its findings align with prior evidence linking calorie restriction to improved brain structure and function in primates.

Importantly, the work highlights white matter as a modifiable target of aging, one that responds to long-term metabolic interventions.

A Metabolic Strategy for Protecting Brain Wiring

This study does not suggest that calorie restriction is a practical or universal solution for humans. Sustained dietary restriction is difficult to maintain and may not be appropriate for all individuals. However, the findings provide valuable insight into the biological pathways that support white matter health during aging.

By identifying how calorie restriction reshapes gene activity in glial cells, the work points toward future strategies that could mimic its benefits without requiring drastic dietary changes. Interventions that preserve cellular energy balance, limit oxidative stress, and restrain chronic inflammation may offer a way to slow brain aging while maintaining the brain’s structural integrity.

Model: Aged male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) enrolled in the National Institute on Aging long-term calorie restriction study, used to model primate brain aging and white matter decline.

Dosage: Chronic dietary calorie restriction of approximately 30% relative to control intake, initiated in early adulthood and maintained continuously for over 20 years without malnutrition.