Staying Hungry Drives Younger Blood, Mayo Clinic Discovers

A well-established life-extending intervention, calorie restriction — eating less food without malnourishment — reduces circulating molecules that may contribute to shortened lifespan and chronic disease.

Highlights:

- Middle-aged adults who reduced their calories by 25% (average of 12%) over 2 years tended to have lower levels of potentially age-driving proteins in their blood.

- These potentially age-driving proteins predicted the incidence of insulin signaling dysregulation.

As part of the most exhaustive and thorough study of its kind, scientists from the Mayo Clinic, a top ranked non-profit healthcare organization, have found that CR effectively reduces proteins associated with age-driving senescent cells.

Senescent cells are thought to drive the aging process by releasing various proteins into the bloodstream that cause body-wide organ damage. Considering that continuous organ damage leads to chronic diseases and high-mortality, diminishing these proteins could delay disease and prolong lifespan.

Senolytics Eliminate Senescent Cells

CR is the most robust life-extending intervention in animals, encouraging scientists to find ways of mimicking CR by repurposing pharmaceuticals or mega-dosing natural molecules. The current Mayo Clinic study suggests that senolytics — compounds that eliminate senescent cells — are such a mimetic.

Corroborating this idea, another Mayo Clinic study showed that senescent cells are associated with shortened lifespan in humans. And now over 30 clinical trials will test the effects of senolytics on age-related diseases like Alzheimer’s, arthritis, and obesity. When complete, these studies may point to senolytics miming the anti-aging effects of eating less.

Study Details

Healthy middle-aged (~38 years old) individuals, 128 by count, were told to reduce their calories by 25% over two years — the calorie restriction (CR) group. Meanwhile, a similar group of 71 individuals were allowed to eat whatever they liked — the ab libitum (AL, Latin for “at one’s pleasure”) group. Both groups were predominantly white (~75%) and female (~70%).

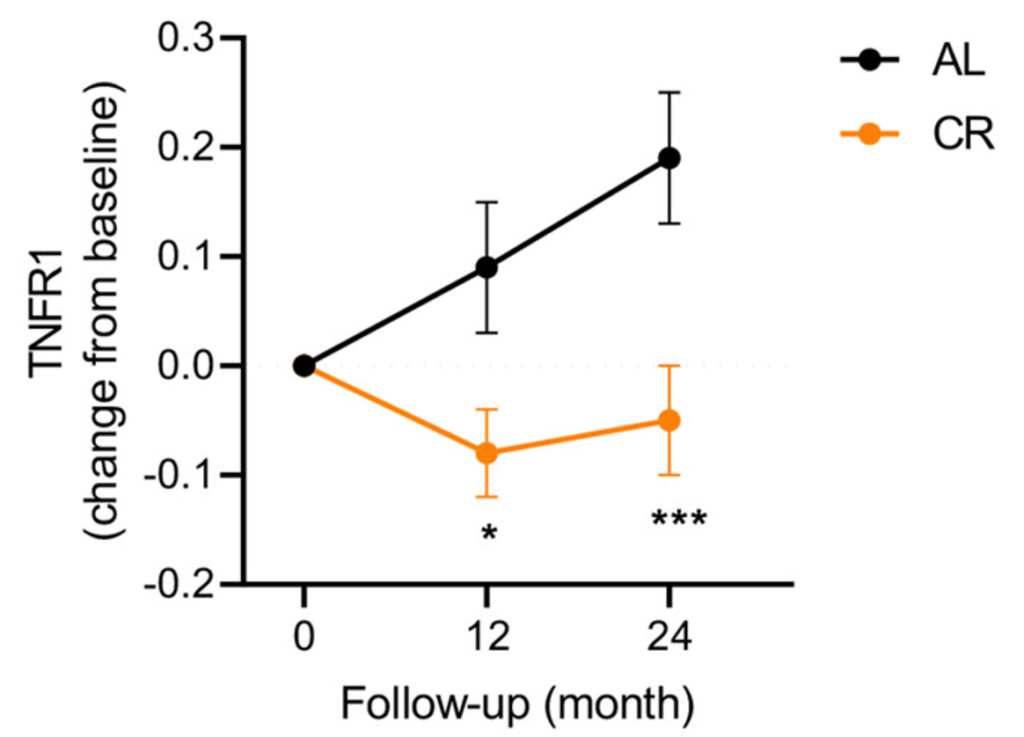

Compared to the AL group, the CR group tended to have fewer senescent cell-associated proteins in their blood. It should be pointed out, however, that the proteins measured were exclusive to senescent cells and could have been secreted by other cell types. Furthermore, whether CR eliminates senescent cells like senolytics was not directly measured by the researchers.

(Aversa et al., 2023 | Aging Cell) Example of a Senescence-Associated Protein Decreasing in Response to CR. After both 12 and 24 months, compared to the ab libitum (AL) group, the calorie restriction (CR) group had lower blood levels of TNFR1, a protein associated with activating cellular inflammatory responses.

Additionally, the Mayo Clinic scientists found that changes in senescence-associated proteins predicted the incidence of insulin resistance, a prerequisite to diabetes. While this prediction does not infer a cause-and-effect relationship, it suggests a mechanism by which CR protects against diabetes and other age-related diseases like obesity. Overall, the authors say,

“In conclusion, our results show that 2 years of moderate CR with adequate nutrient intake reduces biomarkers of cellular senescence in healthy young to middle-aged humans without obesity.”

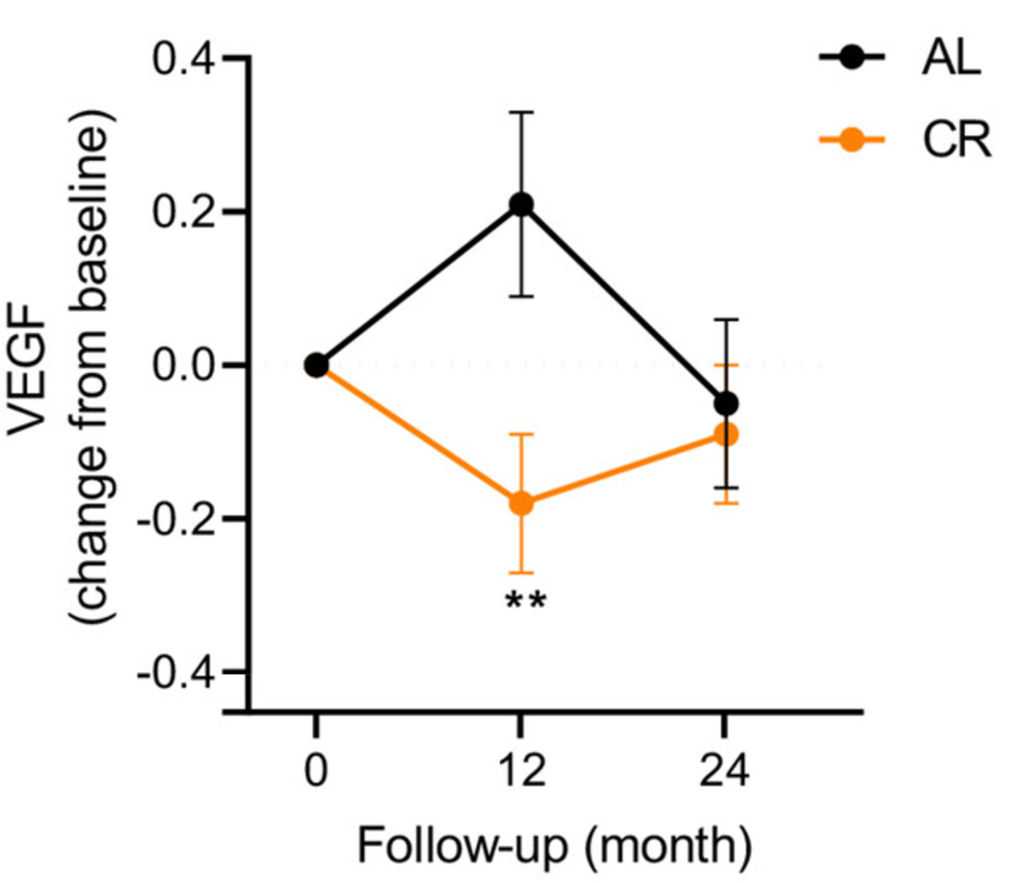

Notably, in both the AL and CR groups, many of the senescence-associated proteins did not show a consistent increase or decrease between the 12- and 24-month follow-up. Many of the differences observed between the AL and CR groups seemed to have been a result of these year-to-year fluctuations.

(Aversa et al., 2023 | Aging Cell) Example of Fluctuations in a Senescence-Associated Protein Leading to Significant Differences. After 12 months, VEGF — a protein associated with new blood vessel formation — increased in the ab libitum (AL) group and decreased in the calorie restriction (CR) group, leading to a significant difference between the AL and CR group. However, after 24 months, the opposite occurred and there was no longer a difference between the AL and CR group.

A shorter study with more testing points could better resolve how these proteins fluctuate with time. For example, a six-month study, where protein measurements are taken each month (six time-points) would show how sporadically senescence-associated proteins change in normal individuals (a group similar to the AL group) and individuals on a calorically restricted diet (a group similar to the CR group).

This short-term study could inform longer-term studies on the number of testing points needed. For example, if it is found that senescence-associated proteins do not significantly fluctuate within six months, a new study could measure these proteins every 6 months from both an AL and CR group for 3 years or longer.

In any case, a better understanding of how and why the blood concentrations of senescence-associated proteins change with time in humans seems necessary.

Participants: Middle-aged adults

Intervention: ~12% calorically restricted diet