German Study Finds Eating Strawberries and Capers Lowers Cholesterol and Inflammation

Older individuals on an anti-aging senolytic diet consisting of strawberries and capers have reduced “bad” cholesterol and inflammation.

Highlights:

- Strawberries and capers contain high levels of senolytics — compounds that eliminate age-promoting (senescent) cells.

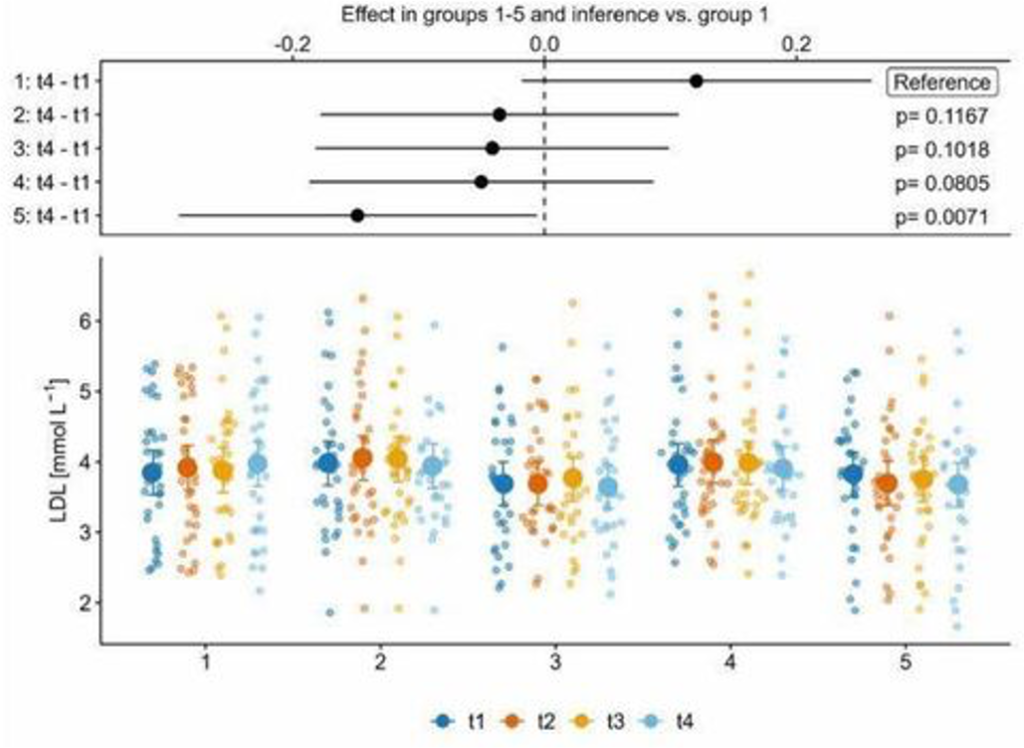

- Older individuals who consumed copious amounts of strawberries and capers saw a reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol after ten weeks.

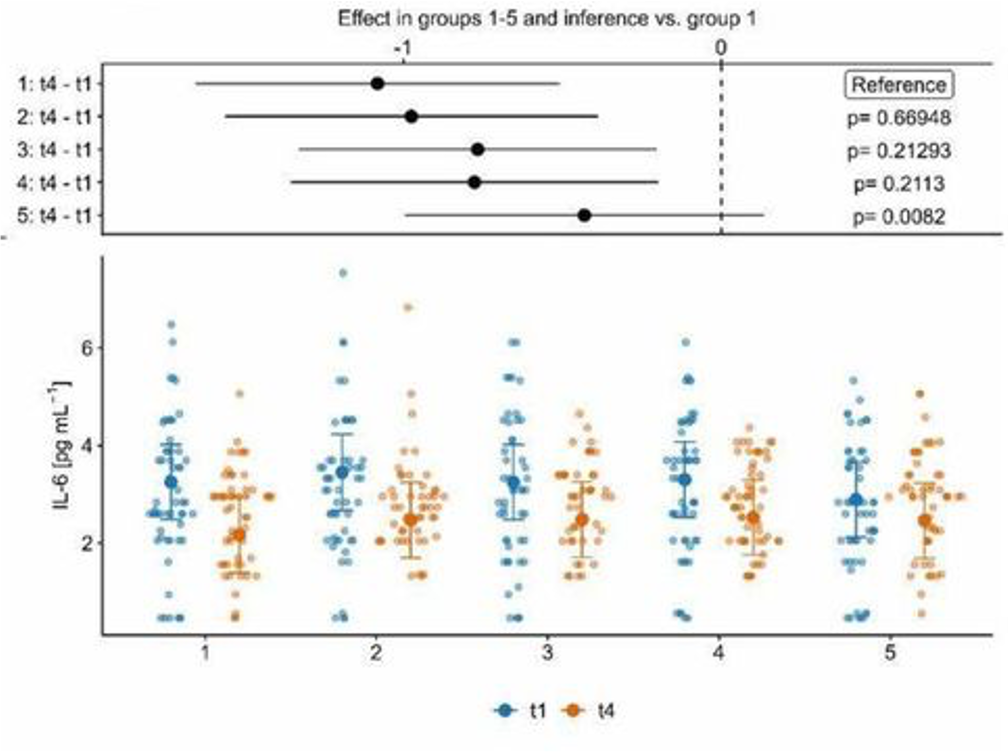

- Ten weeks of the senolytic-containing diet also reduced the pro-inflammatory marker IL-6, among other benefits.

“Fruits and vegetables are good for us” has become a cliche, but the latest aging biology research offers another reason to eat plant-based foods: senolytics. Many plant-based foods contain natural chemicals called polyphenols, some of which act as senolytics, compounds that eliminate senescent cells. Since senescent cells are thought to drive the aging process, consuming senolytic compounds could potentially slow the aging process.

Now, in a preprint from MedRxiv, researchers from Rostock University in Germany report that a polyphenol-rich diet improves cholesterol and inflammation profiles in healthy older individuals. Hartmann and colleagues find that a strawberry and caper-rich diet reduces LDL cholesterol and the pro-inflammatory molecule IL-6. Furthermore, gene analysis supports their hypothesis that the senolytic diet reduces senescent cells.

Strawberries and Capers Lead to Reduced Cholesterol and Inflammation

168 individuals ranging from 50 to 80 years of age were divided into five groups. Group 1, the control group, ate 500 grams of fresh strawberries once a week, considered a moderate amount. The author’s state:

“A placebo was not available, as a convincing placebo for whole, fresh strawberries is not available/practical.”

Groups 2-5 consumed escalating levels of fresh strawberries over ten weeks with a maximum of 750 grams five times per week. In addition to fresh strawberries, groups 3-5 consumed increasing levels of freeze-dried strawberries 3 times per week. Group 5 was the only group to consume capers, with a maximum of 240 grams twice in ten weeks.

The results showed that LDL was lowered by 5.72 mg/dL in the group that consumed the most strawberries in addition to capers (group 5) compared to the group that ate the least amount of strawberries (group 1). For reference, an LDL level above 130 mg/dL is considered high. Additionally, total cholesterol, which includes LDL and “good” high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, decreased in group 5 compared to group 1. These findings suggest that eating enough strawberries and capers can lower cholesterol.

High LDL cholesterol levels are associated with an increased risk for blood vessel occlusions that can lead to heart complications like heart attack and stroke. Since most individuals experience such heart complications in old age, heart disease is considered an age-related disease. Thus, reducing LDL cholesterol could result in less plaque buildup, potentially postponing or preventing heart complications.

Inflammation is a fundamental “hallmark” or feature of aging and disease that contributes not only to blood vessel plaque buildup, but the gradual decline of multiple organs and tissues. Senescent cells contribute to inflammation, so a diet high in senolytics could reduce inflammation by eliminating senescent cells. Hartmann and colleagues found that the inflammatory molecule IL-6 was reduced in group 5 compared to group 1, suggesting that strawberries and capers can alleviate inflammation.

In addition to measuring biomarkers like LDL and IL-6 from the blood of each participant, Hartmann and colleagues analyzed the genes from the white blood cells of a subset of participants. The results corroborated with the IL-6 data, showing the increased activation of genes involved in inflammation. Genes involved in mitochondrial and immune health were also increased. Furthermore, specific cell death genes were elevated, suggesting the elimination of senescent cells.

Concentration of Senolytics in Strawberries a Tiny Dose?

To determine which senolytic polyphenols could be contributing to the benefits of strawberry consumption, Hartmann and colleagues measured the levels of the senolytics quercetin and fisetin from a sample of strawberries and capers used in the study. While fisetin was not detected, there was up to about 14 mg/kg of bioavailable quercetin in the strawberries and up to about 108 mg/kg in the capers.

This means that with the maximum portion of 950 grams of strawberries and 240 grams of capers consumed by group 5, each participant could have consumed about 40 mg of quercetin. This is a small dose compared to the recommended dosage for quercetin supplements, which can be as high as 500 mg. However, there is not enough evidence to proclaim the optimal dosage of quercetin in treating inflammation or any other ailment. Thus, 40 mg seems to be sufficient, at least for some measures.

Ultimately, strawberries have a lot more to offer than quercetin, and it is unclear how large of a role quercetin played in reducing LDL and inflammation. Strawberries contain many anti-inflammatory molecules that may operate synergistically. Furthermore, strawberries contain LDL-lowering chemicals like anthocyanins and phytosterols, which could also have contributed to the beneficial effects of the strawberry-rich diet.

Karl’s Strawberry Farm and Limitations

It should be pointed out that the study was funded in part by Karls Erdbeerhof, who provided the strawberries used in the study. While this is not a limitation of the study, there are a few limitations outlined by the authors. One limitation is that the participants knew when they were part of one of the intervention groups, which may have generated a stronger-than-usual placebo effect. Another limitation is that the participants may have replaced unhealthy foods with the strawberries they had to eat. Overall, the authors state:

“Our study contributes some insights towards designing and selecting nutritional interventions for maximum effect, and encourages future work to define high-effect nutritional interventions.”

Participants: Healthy individuals aged 50 to 80 years

Dosage (maximum): 750 grams of fresh strawberries five times per week, and 200 grams of freeze-dried strawberries and 240 grams of capers in olive oil three times a week