How Soviet-Era Scientists Helped Lay the Foundation for Modern Aging Research

A new reflective essay explores how two generations of Russian scientists reshaped the way we think about aging.

Highlights

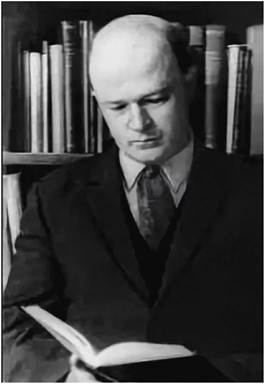

- From the late 1940s until his death in 1994, Russian scientist Vladimir Dilman developed the idea that a brain region called the hypothalamus becomes less sensitive to feedback signals, driving aging.

- Dilman’s son, Mikhail Blagosklonny, went on to formulate a new theory based on Dilman’s ideas, arguing that growth-promoting cellular pathways, such as mTOR, continue to drive cell growth and activity after development is complete, to drive aging.

During his career, Mikhail Blagoskonny regarded aging not as a slow decay but as biological processes stuck in overdrive. Now, in an article published in Aging, an appreciation for his ideas on aging, deeply rooted in the work of his father, Soviet-era Russian scientist Vladimir Dilman, has gained recognition.

In the article, which is a reflective essay, biogerontologist Aleksei G. Golubev of the N.N. Petrov National Medical Research Center of Oncology in Russia traces how Dilman’s views on aging helped shape Blagosklonny’s theory of aging. In that regard, Dilman’s view holds that aging stems from a brain region, called the hypothalamus, becoming less sensitive to feedback signals. Blagosklonny’s theory translated the logic of an anatomical hub of aging (the hypothalamus in this case) to the molecular scale. At the molecular level, Blagosklonny argued that cellular growth pathways, such as mTOR, act as aging hubs and keep driving cell growth and activity long after the completion of development.

While relaying this insight, Golubev makes a notable point with broad implications: much of what people consider modern aging research rests on the foundations that under-cited and overlooked Soviet-era scientists laid. This means that some of the fundamental ideas that modern aging researchers use to decipher mechanisms of aging were initially developed behind the former Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain—the term used for the political, military, ideological, and geographical barrier dividing Soviet-controlled Eastern Europe and the West.

Aging as Overactivation, Not Functional Decline

Conventional theories view aging as a progressive breakdown of physiological function. Along these lines, damage accumulates, cellular functions wear down, and physiological systems fail.

Somewhat contrastingly, aging in Dilman’s theory of aging (known as “elevation theory”) begins when the hypothalamus—a key brain region that regulates hormones, metabolism, and reproduction—progressively becomes less sensitive to feedback signals. For compensation, the body elevates hormone and metabolite levels. Thus, the physiological mechanisms that once served to support growth and adaptation eventually push the organism into a state of hormonal and metabolic overdrive.

Blagosklonny’s theory (the “hyperfunction theory”) translated Dilman’s rationalization from an anatomical structure in the brain to the molecular level. Accordingly, Blagosklonny argued that growth-promoting pathways, such as mTOR, are necessary during development to produce a mature organism. However, these pathways drive cell growth and activity long after development is complete. Thus, aging, according to this view, arises when growth programs do not fully switch off. Cells and tissues undergo too much growth and activity, which was beneficial during development, leading to conditions like high blood pressure, organ hypertrophy, and cancer.

In the essay, Golubev emphasizes that the parallels between the two theories may not be entirely coincidental—Dilman was indeed Blagosklonny’s father. Thus, while Dilman framed the hypothalamus as a master regulator with a sensitivity threshold that keeps rising, which subsequently results in elevated hormone and metabolite levels, decades later, Blagosklonny described mTOR as a kind of “molecular hypothalamus.” In Blagosklonny’s view, mTOR integrates nutrient, growth, and stress signals and drives age-related pathology through overactivation, similar to how a hypothalamus with reduced sensitivity acts as an anatomical hub that drives aging in Dilman’s theory. Both theories portray aging not as loss simply from damage but as chronic, amplified functional activity that overshoots developmental goals.

Rediscovering the Origins of Modern-Day Conceptions of Aging

In the essay, Golubev also points out that many themes central to modern-day aging research, such as links between metabolic syndrome and cancer and the use of antidiabetic medications like metformin as anti-cancer and anti-aging agents, were explored in Dilman’s Soviet-era laboratory. This research occurred long before such ideas became more mainstream. Moreover, later discoveries that drugs used against aging, like rapamycin, act, in part, through suppressing mTOR signaling, provided evidence supporting Blagosklonny’s hyperfunction model of aging, derived from Dilman’s hypothalamic elevation theory.

Because much of the Soviet-era research was published in Russian, behind the former Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain and before digital indexing, Dilman’s and Blagosklonny’s work remains sparsely cited in today’s aging research literature. Golubev not only sees this as a historical oversight but something that should be viewed with caution. Along these lines, he conveys that when researchers forget early contributions, especially those from laboratories in non-Western nations, research fields risk repeating old ideas and mistakes without learning from prior insights.