New Aging Theory Helps Build the Case for Devices That Activate Key Nerve

A new aging theory posits that an increasing age-related imbalance between collections of nerves triggering “fight or flight” and “rest and repair” responses underlies core aging processes.

Highlights

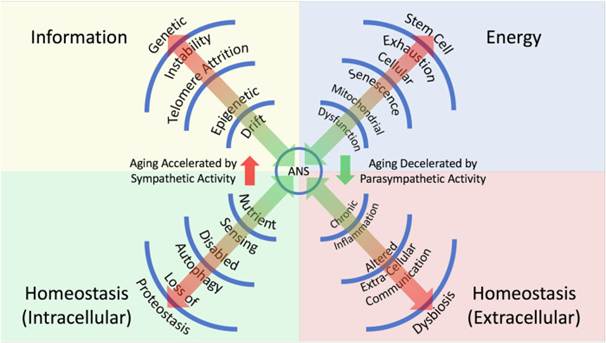

- The aging theory contends that the imbalance between the sympathetic nervous system (involved in fight or flight responses) and the parasympathetic nervous system (involved in rest and repair) contributes to multiple hallmarks of aging.

- To remedy this imbalanced activity, scientists propose vagus nerve stimulation, where a device delivers electrical impulses via the neck or ear to a key nerve, activating the parasympathetic nervous system.

Some of the earliest theories of aging, such as one proposed by Max Rubner in 1908, stipulated that the faster an organism’s metabolism, the shorter its lifespan. Max Rubner’s idea also states that the total metabolic energy an organism uses over a lifetime is about the same across species, implying that an organism’s rate of energy expenditure determines its lifespan. For example, a small organism, such as a squirrel, with a relatively high metabolism, lives a dramatically shorter life than an elephant, which is much larger and has a lower metabolic rate per gram of body weight.

Historically, other theories of aging have followed, attributing aspects of aging to things like the accumulation of deleterious molecules called free radicals in cells, the shortening of protective caps composed of DNA at the ends of chromosomes, and inflammation. Now, as published in NPJ Aging, Tremblay and colleagues from the University of British Columbia in Canada provide a rationale for a new theory of aging. This theory contends that a dysregulated imbalance between the sympathetic nervous system (comprised of nerves that trigger a “fight-or-flight” response) and the parasympathetic nervous system (comprised of nerves that trigger a “rest and relax” response) is a unifying process that accounts for changes related to aging.

Background on the Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous Systems

The sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system, along with the enteric nervous system that controls digestion, make up what is called the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary bodily functions, like heart rate, blood pressure, alertness, and digestion. Interestingly, the autonomic nervous system works intimately with the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) to maintain the balance (homeostasis) of almost all internal aspects of physiological function.

Regarding the sympathetic nervous system, this arm of the autonomic nervous system coordinates stress responses to, for example, cognitive, emotional, and physical stressors, which disrupt homeostasis. In doing so, the sympathetic nervous system orchestrates “fight or flight” physiological responses. Accordingly, the sympathetic nervous system’s responses oppose the loss of homeostasis. For example, a physical stressor, such as an encroaching tiger, would stimulate a sympathetic nervous system response along the lines of an increased heart rate, dilated pupils, and more rapid breathing to facilitate some sort of escape.

The parasympathetic nervous system, another arm of the autonomic nervous system, also works to counteract a loss of homeostasis through its coordination of “rest and response” reactions. Examples of these kinds of responses are a slowing heart rate and increased digestion after a meal.

How Sympathetic Nervous System Overactivation Relates to Aging

Importantly, chronic sympathetic nervous system activation without recovery via the parasympathetic nervous system, also referred to as chronic stress, can drive excessive divergence from physiological stability and homeostasis. In fact, several studies highlight an increasing physiological imbalance that occurs due to chronic sympathetic nervous system activation during aging. As such, a hyperreactive sympathetic nervous system has been tied to pro-inflammatory conditions and enhanced inflammaging—an age-related, low-grade, sterile, systemic inflammatory state. As far as how this might affect aging goes, inflammaging has gained notoriety as an important risk factor for several age-related diseases in humans.

An overactive sympathetic nervous system also hinders the body’s mechanisms for counteracting inflammaging, a phenomenon arising through diminished blood flow, altered hormone signaling, and nerve damage. These factors lead to a reduced responsiveness to stress and an increased vulnerability to age-related diseases.

This set of circumstances led Tremblay and colleagues to contend that an age-related imbalance between sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system activation facilitates physiological divergence from homeostasis. In turn, this divergence from homeostasis drives multiple hallmarks of aging, including genetic instability, as well as metabolic and immune dysfunction, through alterations in cellular pathway signaling.

Restoring Parasympathetic Nervous System Activation to Slow Aging

Balancing divergent physiological homeostasis arising from sympathetic nervous system overactivation via activation of the parasympathetic nervous system has long been recognized as a potential means to slow aging. As such, various world cultures have adopted healing and social practices, as well as techniques like yoga, to increase parasympathetic nervous system activation.

Recently, technologies that directly reactivate the parasympathetic nervous system have been developed as well. Such technologies entail invasive vagus nerve stimulation (where a device that sends electrical pulses through the vagus nerve near the neck is surgically implanted) as well as non-invasive hand-held devices that apply electrical stimulation to the vagus nerve.

As far as the hand-held devices for vagus nerve stimulation go, they can work in one of two different ways. For example, transcutaneous cervical vagus nerve stimulation involves placing an electrical device on the skin of the neck over the vagus nerve to send electrical pulses, and auricular vagus nerve stimulation entails a similar procedure using electrodes clipped onto the ear. Intriguingly, these procedures have been developed to treat multiple conditions, like epilepsy, depression, migraines, and schizophrenia. However, their application to slow aging arose sometime in the late 2010s.

As far as research goes on vagus nerve stimulation, studies suggest that regular application of the procedure improves immune function and restores dysfunctional mitochondria (the cell’s powerhouses). Since an age-related loss of immune function and mitochondrial dysfunction are established hallmarks of aging, some researchers believe that activating the parasympathetic nervous system with vagus nerve stimulation may have protective effects against aging. In line with their theory of aging, Tremblay and colleagues believe this may be the case through vagus nerve stimulation’s restoration of an age-related imbalance between activation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

“Collectively, the data support a unifying hypothesis in which the balance between [sympathetic nervous system] and [parasympathetic nervous system], through multiple molecular and cellular mechanisms, integrates the hallmarks of aging and may serve as an important therapeutic target,” say Trembaly and colleagues in their publication. “Thus, studies examining the longevity-enhancing potential of [vagus nerve stimulation] are warranted.”