Intermittent Fasting Enhances Long-Term Memory and Adult Neurogenesis in Mice

Research from King’s College London suggests that intermittent fasting has the potential to be a potent cognitive enhancer

Highlights

· Intermittent fasting is more effective than calorie restriction in promoting long-term memory retention and increasing the generation of new brain cells in adult mice.

· The longevity gene Klotho is upregulated by intermittent fasting and is required for neurogenesis in the mice and cultured human adult brain stem cells.

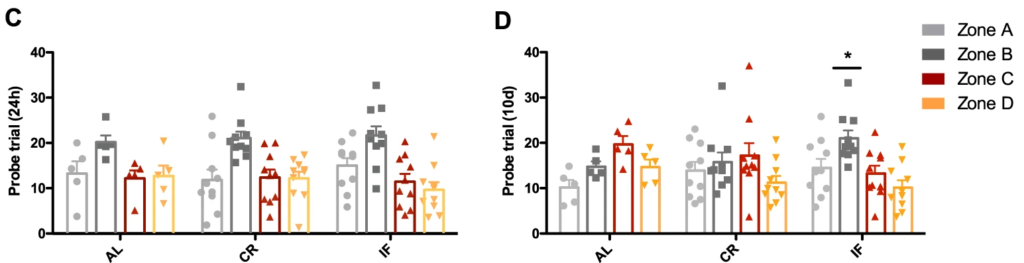

Calorie restriction and intermittent fasting are two established dietary paradigms that extend life- and health-span across species. Now, researchers from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College London demonstrate that with an overall 10% matched-energy intake, intermittent fasting in the form of every-other-day feeding is superior to daily calorie restriction in enhancing long-term memory performance in mice. Pereira Dias and colleagues provide evidence that this enhancement is associated with increased adult hippocampal neuron production (neurogenesis) and activity of the longevity gene Klotho, which was also shown to be required for neurogenesis in cultured human adult brain stem cells.

Calorie restriction vs. intermittent fasting

Calorie restriction, typically defined as a 10–40% total reduction in daily calorie intake, and intermittent fasting, typically involving every-other-day feeding, are two established dietary paradigms that extend life- and health-span across species. In mice, a recent study demonstrated that adoption of 30% calorie restriction or a single meal feeding strategy for 10 months enhanced longevity and health status. Adherence to calorie restriction and intermittent fasting regimens also improves learning and memory in different models.

Notably, calorie restriction and intermittent fasting have been conflated in the literature with many studies reporting the beneficial effects of calorie restriction on measures of inflammation, neurodegeneration, brain plasticity, learning, and motor performance, when in fact forms of intermittent fasting were used in these studies to bring about overall reductions in calorie intake. However, one of the first studies to dissociate intermittent fasting from CR demonstrated that mice in the intermittent fasting paradigm did not reduce their overall food intake and maintained body weight.

Despite the positive effects of calorie restriction and intermittent fasting in neurodegenerative and affective conditions, the specific behavioral contributions and mechanisms that differentiate both interventions remain largely unknown. Answering these questions is pivotal to adapting these regimens to human populations, given the challenges of adhering to a long-term calorie restriction regimen when compared to the improved adherence to variations of the intermittent fasting paradigm.

Intermittent fasting is superior to calorie restriction in improving brain function

Pereira Dias and colleagues addressed whether the beneficial effects of intermittent fasting on cognition are due to a decrease in the total amount of calories consumed or to the increased interval between meals. The King’s College research team demonstrated that, with an overall 10% matched-energy intake, intermittent fasting in the form of every-other-day feeding is superior to daily calorie restriction in enhancing long-term memory performance in mice.

This enhancement is linked with an increased adult generation of new brain cells in the hippocampus — a brain region key to learning and memory. This adult hippocampus neurogenesis was dependent on the activity of the longevity gene Klotho. What’s more, Klotho was also necessary for neurogenesis stemming from cultured human brain stem cells.

Intermittent Fasting Activates Klotho for Neuron Production

Dr. Sandrine Thuret from King’s IoPPN said, “We now have a significantly greater understanding as to the reasons why intermittent fasting is an effective means of increasing adult neurogenesis. Our results demonstrate that Klotho is not only required, but plays a central role in adult neurogenesis, and suggests that IF is an effective means of improving long-term memory retention in humans.”

Lead author Dr. Gisele Pereira Dias from King’s IoPPN said, “In demonstrating that intermittent fasting is a more effective means of improving long term memory than other calorie-controlled diets, we’ve given ourselves an excellent means of going forward. To see such significant improvements by lowering the total calorie intake by only 10% shows that there is a lot of promise.”

How Do We Apply Intermittent Fasting to Humans?

It is worth noting, though, that studies in humans are warranted to determine the most feasible forms of intermittent fasting that could render improved cognitive performance in this population. This is of particular relevance considering that adherence to the form of intermittent fasting adopted in the present study might be challenging to promote in human populations.

Evaluating the effects of other fasting paradigms, such as adopting longer periods of food intake between fasting days or time-restricted feeding paradigms, should give us valuable answers as to how to promote realistic adherence to fasting without compromising its positive effects on markers of neuroplasticity.