Life-Extending Drug Rapamycin Protects Against DNA Damage: New Oxford Study

Inhibiting a key age-associated cellular signaling enzyme, called mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin), counteracts DNA damage and immune system aging in humans.

Highlights

- Inhibiting mTOR reduces DNA damage in vital white blood cells called T cells.

- Rapamycin, which inhibits mTOR, doubles the survival rate of T cells.

- Supplementing with rapamycin reduces T cell DNA damage in older adults.

Of all the anti-aging interventions, mTOR inhibition is the most well-established to date. Inhibiting mTOR has been shown to extend the lifespan of all species tested, while also extending healthspan—the duration of time spent in good health. However, a clear explanation for why mTOR inhibition leads to these profound effects is lacking.

This has caught the attention of Dr. Kell and her colleagues at the University of Oxford and the University of Nottingham in England. In a new study published in Aging Cell, Dr. Kell and colleagues reveal that mTOR inhibition exerts its anti-aging effects by protecting against DNA damage and immune cell dysfunction. Considering that dysfunctional immune cells promote body-wide aging, this could explain how inhibiting mTOR extends lifespan and healthspan.

Inhibiting mTOR Reduces White Blood Cell DNA Damage

Our bodies house a variety of immune cells, also known as white blood cells. Among these immune cells are T cells, which play a vital role in eliminating foreign invaders. However, dysfunctional T cells, particularly those with DNA damage, are increasingly linked to cancer, aging, autoimmunity, and immune dysfunction. This makes dysfunctional T cells an ideal target for anti-aging interventions.

In a landmark 2014 study, inhibiting mTOR was shown to improve immune cell function in older adults, notably reducing T cell dysfunction. With this in mind, Kell and colleagues sought to determine if inhibiting mTOR could reduce T cell DNA damage. To induce DNA damage, they exposed human T cells to an antibiotic called zeocin, which causes double-strand breaks. Double-strand breaks are essentially cuts in DNA’s double helix, and embody the worst type of DNA damage.

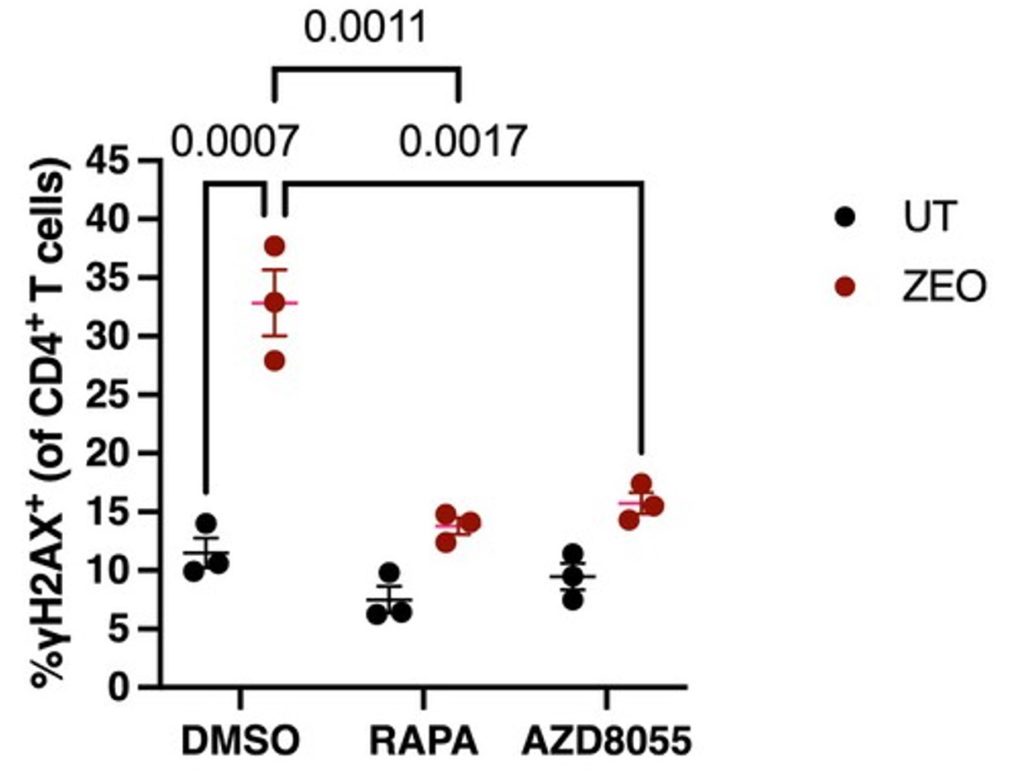

The researchers showed that zeocin effectively elevated DNA damage, namely double-strand breaks, in human T cells. Then, to test the effect of mTOR inhibition, they treated the damaged T cells with two different mTOR inhibitors: rapamycin and AZD8055. Remarkably, inhibiting mTOR with these two compounds led to a significant reduction in T cell DNA double-strand breaks. These findings support the idea that mTOR inhibition alleviates T cell DNA damage.

Inhibiting mTOR Increases White Blood Cell Survival

Through further experimentation, Kell and colleagues explored how inhibiting mTOR can reduce T cell DNA damage. mTOR is usually activated by molecules that signal nutrient abundance, such as the amino acid leucine, and is therefore considered a nutrient sensor. It is also activated in response to resistance exercise. When mTOR is activated, it orchestrates the cellular processes that stimulate growth, including muscle growth.

To maintain growth, activated mTOR ramps up protein synthesis to generate proteins. In contrast, inhibiting mTOR reduces protein synthesis, which could potentially lead to a reduction in DNA damage proteins. Namely, the marker the researchers used to measure DNA damage (γH2AX) is a protein that could have been reduced by mTOR inhibition. However, the researchers found that inhibiting mTOR did not reduce protein synthesis in damaged T cells.

The researchers next explored changes in autophagy—the system our cells use to degrade and recycle damaged cellular components. Autophagy can protect against DNA damage by improving mitochondrial health and reducing the generation of free radicals—molecules capable of directly causing DNA damage. However, while mTOR inhibition improved autophagy, it also reduced DNA damage independent of autophagy. Thus, mTOR does not appear to reduce T cell DNA damage by lowering protein synthesis or increasing autophagy.

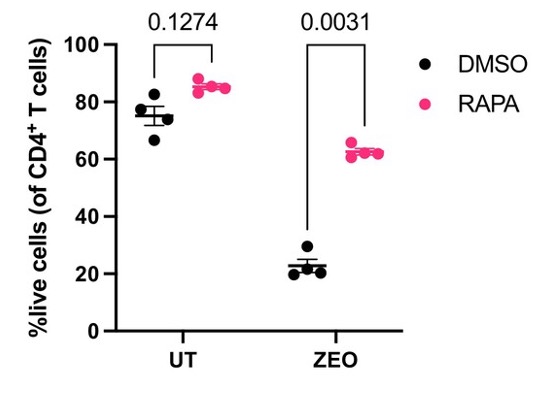

Upon performing a more direct measurement, Kell and colleagues proposed that inhibiting mTOR protects against DNA damage by enhancing DNA integrity. They also measured T cell survival in response to 24 hours of DNA-damaging zeocin exposure. Strikingly, zeocin killed about 80% of T cells, demonstrating the lethality of double-strand breaks. However, inhibiting mTOR greatly improved survival, with 40% of T cells surviving after being exposed to zeocin for 24 hours.

mTOR Activation and DNA Damage in Volunteers

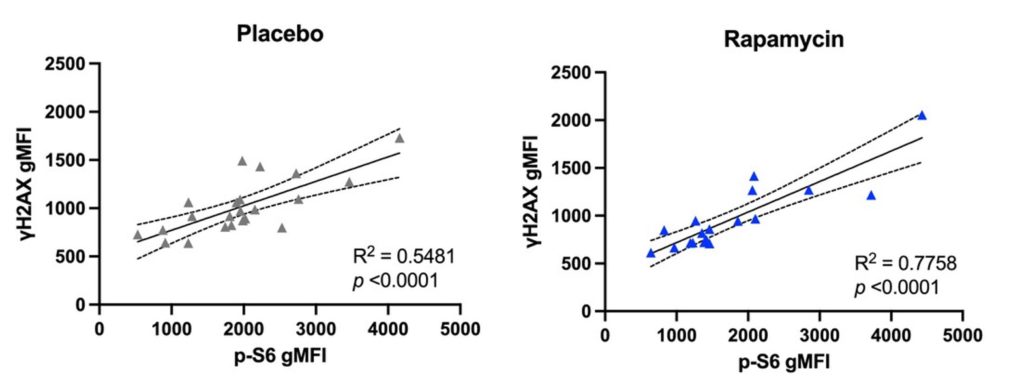

In examining immune cells from human donors, Kell and colleagues found that, compared to young adults, older adults feature more immune cells with DNA damage, mTOR hyperactivation, and cellular senescence, which are cellular drivers of aging. Considering the amalgamation of their results, the researchers next studied the impact of inhibiting mTOR in older male volunteers. To do so, four of the volunteers took 1 mg/day of rapamycin while five took a placebo for 4 months.

The results revealed a strong correlation between mTOR activation and DNA damage in the T cells of both groups, indicating that hyperactivation of mTOR contributes to DNA damage. However, in the rapamycin group, T cell DNA damage and mTOR hyperactivation were reduced, along with markers of cellular senescence, a major driver of aging. These preliminary results suggest that supplementing with a low dose of rapamycin can minimize T cell DNA damage and senescence by inhibiting the mTOR pathway.

Inhibiting mTOR to Improve Health and Longevity

The work of Kell and colleagues suggests that inhibiting mTOR can counteract immune system aging by reducing DNA damage and senescence in T cells. However, the authors of the study point out several limitations:

Inhibiting DNA damage and cellular senescence may alter the normal physiological functioning of the immune system. For example, when cells are infected with a virus, they become senescent cells and are promptly removed by the immune system. It follows that inhibiting cellular senescence may reduce the immune system’s ability to remove harmful cells.

Senescent cells also play a crucial role in tissue regeneration, suggesting that inhibiting mTOR could interfere with wound healing, which is impaired in older individuals. Furthermore, DNA damage inherently occurs during immune cell development, including the development of T cells. Thus, inhibiting DNA damage could interfere with immune cell maturation, which could reduce the immune system’s ability to defend against foreign invaders.

With that being said, based on the results, mTOR inhibition does not appear to completely block DNA damage and cellular senescence. Still, more studies will be necessary to determine if mTOR inhibition does negatively alter the beneficial functions of the immune system.

Participants: Older male adults around the age of 60

Dosage: 1 mg/day of rapamycin for 4 months