Monoclonal Antibodies: New Hope for Reversing Aging?

Monoclonal antibodies, already in clinical use, show promise against drivers of cellular aging, including senescent cells and inflammation.

Highlights

- Synthetic monoclonal antibodies are being designed to target the root causes of aging, including senescent cells and inflammation.

- Some antibodies, such as donanemab, are already approved by the FDA to target the age-related disorder, Alzheimer’s disease.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are an emerging game-changer in the field of health and longevity. Unlike broad-spectrum drugs that can affect many parts of the body, mAbs are designed with exquisite specificity. Their precision minimizes side effects and maximizes therapeutic impact, opening up unprecedented possibilities for treating age-related diseases.

What Drives Aging?

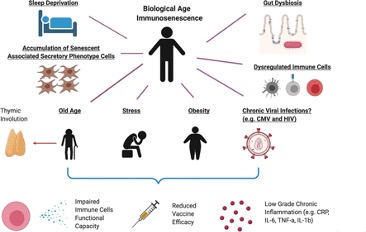

Understanding the fundamental processes that contribute to aging will aid in truly appreciating the advantages of mAbs. Scientists have identified several key biological mechanisms that, over time, lead to the decline of our bodies and increased susceptibility to diseases. These include:

- Cellular Senescence: As we age, senescent cells accumulate in our tissues, releasing inflammatory chemicals that damage surrounding healthy cells. While they initially act as a protective mechanism against cancer, their long-term presence contributes to tissue dysfunction and chronic inflammation.

- Inflammaging: Unlike the transient inflammation triggered by infection or injury, inflammaging is a persistent, low-grade, systemic inflammation that simmers throughout the body as we get older. It’s a silent contributor to a host of age-related diseases, from heart disease to neurodegenerative disorders.

- Immunosenescence: Our immune system, our body’s defense force, also ages. It becomes less effective at fighting off infections, recognizing and destroying cancer cells, and responding to vaccines. This decline leaves us more vulnerable to illness.

- Loss of Proteostasis: Our cells are constantly building, folding, and breaking down proteins. As we age, this intricate balance, known as proteostasis, falters. Misfolded or damaged proteins accumulate, leading to cellular dysfunction and contributing to diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s.

- Advanced Glycation End-products (AGEs): These are harmful compounds formed when sugars react with proteins or fats in our bodies. They build up over time, stiffening tissues and contributing to inflammation, playing a role in diabetic complications and kidney disease.

- Dysregulated Nutrient Sensing: Our bodies have sophisticated systems to sense nutrients and regulate growth. In youth, these pathways are vital for development. However, their overactivation in later life can contribute to cancer and metabolic disorders.

Efforts to combat these drivers of aging have focused on lifestyle changes or small-molecule drugs. However, mAbs offer a more targeted and potentially more effective approach.

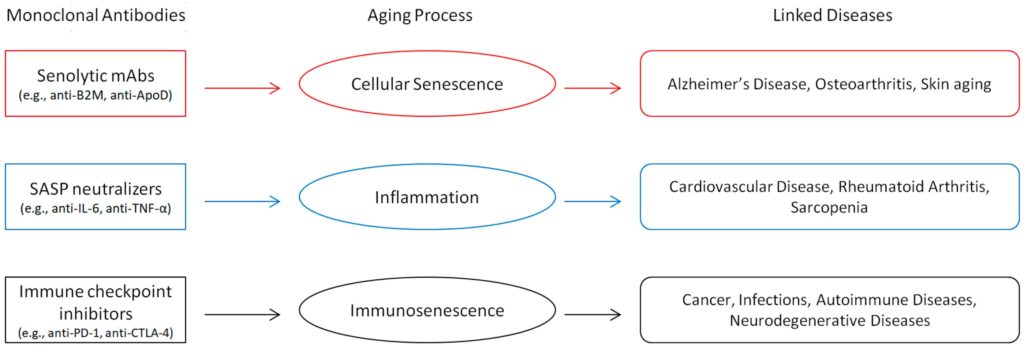

The Three Classes of Antibody Therapy

mAbs can be divided into distinct classes, each with a unique strategy to combat the various aspects of aging:

Class One: Senolytics

These mAbs are designed to recognize unique markers on the surface of senescent cells, delivering a targeted blow that eliminates them while sparing healthy cells. By clearing these harmful cells, senolytic mAbs can reduce chronic inflammation and restore tissue function, potentially offering new hope for conditions like osteoarthritis, Alzheimer’s, and skin aging.

Class Two: SASP Neutralizers

Senescent cells actively secrete a cocktail of pro-inflammatory chemicals known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). This SASP fuels the chronic, low-grade inflammation that characterizes inflammaging. SASP neutralizers are mAbs designed to intercept and neutralize these inflammatory molecules, which are linked to heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and sarcopenia, the age-related decline in muscle mass and strength.

Class Three: Immunity Rejuvenators

Immune checkpoints become overactive in older individuals, hindering the immune system’s ability to fight off threats. By inhibiting immune checkpoints, mAbs can reactivate tired immune cells and enhance their ability to detect and destroy cancer cells and pathogens. This approach, initially revolutionized cancer immunotherapy, is now being explored for its broader potential in autoimmune diseases, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Targeting Other Aging Hallmarks

The Protein Problem

Loss of proteostasis plays a key role in the development of neurodegenerative diseases. Scientists have developed anti-amyloid mAbs, for example, that specifically target and help clear these problematic protein aggregates from the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Three such mAbs (i.e., aducanumab, lecanemab, and donanemab) were recently approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s. However, these mAbs can be very expensive and induce serious side effects. For example, Lilly is charging $32,000/year for donanemab, which is known to trigger brain hemorrhaging in some individuals.

The Sugar Scourge

AGEs contribute to tissue damage, inflammation, and various age-related disorders, particularly in individuals with metabolic issues like diabetes. New AGE-targeting mAbs are being designed to identify and bind to these modified proteins, facilitating their removal by the immune system. This strategy aims to reduce the inflammatory effects of AGEs, potentially offering new treatments for diabetic complications and skin aging.

Rebalancing Nutrient Sensing

Our cells have sophisticated systems that sense nutrient availability and regulate growth, such as the mTOR system. While crucial for development in our younger years, the persistent overactivation of these growth-promoting pathways in later life can contribute to diseases like cancer, metabolic syndrome, and neurodegeneration. Researchers are exploring mAbs that can modulate these systems to improve metabolic health in older individuals.

Challenges and Considerations

Like all powerful medicines, mAbs can have side effects, particularly in older adults with compromised organs and immune systems. For instance, senolytic mAbs, while effective at clearing senescent cells, can sometimes lead to issues like thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) or even hinder wound healing, as some senescent cells play a role in tissue repair.

Similarly, immune checkpoint inhibitors, while revolutionary in cancer treatment, can sometimes trigger adverse events in older patients, leading to conditions like colitis or pneumonitis. Another challenge is the blood-brain barrier, a protective shield around our brain, that becomes more permeable with age. Bypassing the blood-brain barrier might allow more therapeutic antibodies to reach the brain for neurodegenerative diseases.