Psilocybin Increases Cellular Lifespan and Boosts Survival in Aged Mice

New research shows low-dose psilocybin extends cellular lifespan by up to 57%, preserves telomeres, reduces senescence, and boosts survival in aged mice.

Highlights:

- Daily treatment with low-dose psilocybin extended the cellular lifespan of human cells by up to 57%, while also reducing markers of cellular aging such as senescence-associated β-galactosidase, p16, and p21, indicating its potential as an anti-aging agent.

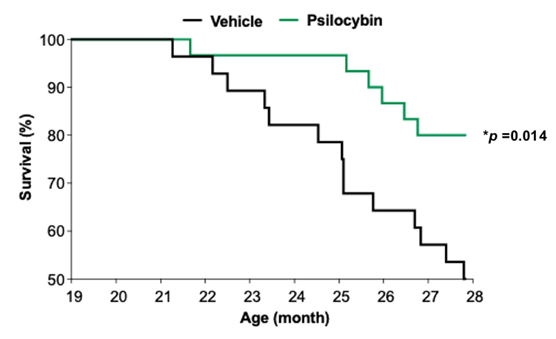

- Psilocybin treatment increased survival rates in aged mice from 50% to 80%, with visible improvements in fur texture and pigmentation, suggesting its potential to influence multiple aging pathways and promote healthier aging.

Psychedelic therapies have long captured the public imagination for their ability to unlock altered states of consciousness. But a new study suggests that psilocybin, the active compound in magic mushrooms, may have effects that go far beyond the brain. Researchers have found that low-dose psilocybin can extend the cellular lifespan of human cells in the lab and improve survival rates in aged mice.

The findings come from a preclinical study published in npj Regenerative Medicine. Although still in the early stages, the work suggests that psilocybin may hold promise as a novel longevity-enhancing molecule that targets some of the cellular hallmarks of aging.

Psilocybin Extends Cellular Lifespan and Reduces Senescence

The research team first tested how psilocybin affects aging at the cellular level by applying the compound to human fibroblasts. These connective tissue cells play a key role in skin health and wound healing. As these cells age, they stop dividing and enter a dysfunctional state called senescence. Senescent cells accumulate with age and release inflammatory molecules that can drive tissue damage and age-related diseases.

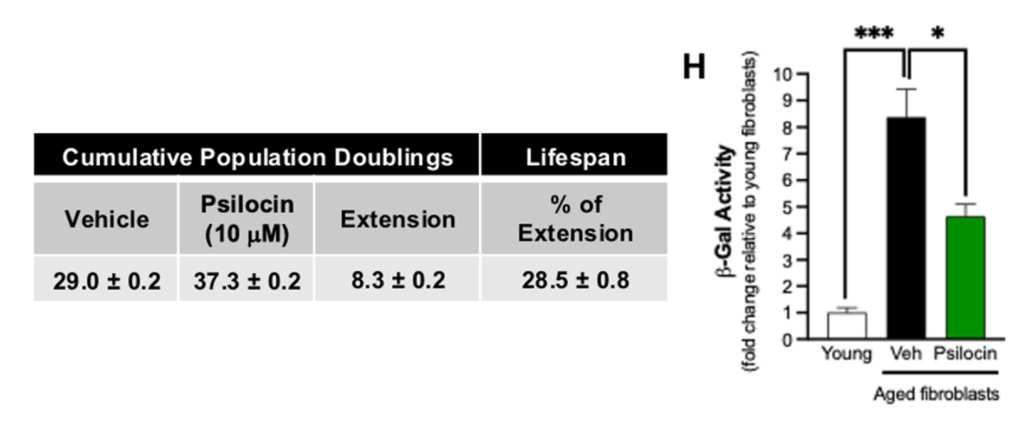

In their experiments, the researchers treated aged fibroblasts with two different concentrations of psilocybin. Cells exposed to 10 micromolar (μM) psilocybin experienced a 29% increase in cellular lifespan, while cells treated with 100 μM of the compound showed a striking 57% extension in lifespan compared to untreated controls. These results point to a powerful dose-dependent anti-senescence effect.

Further tests revealed that psilocybin-treated cells also had significantly lower activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal), a well-established marker of aging cells. The levels of two other key senescence markers, p16 and p21, also decreased in response to psilocybin treatment. Together, these findings indicate that the compound not only delays the aging process in cells but also reduces the burden of senescent cells.

Psilocybin Helps Preserve Telomeres and Boosts Longevity Genes

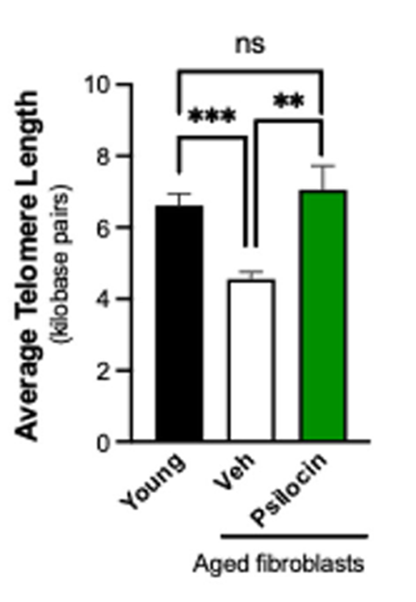

Another important finding involved the preservation of telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that shorten as cells divide. Telomere shortening is a hallmark of cellular aging and plays a role in age-related decline across multiple tissues. Psilocybin helped preserve telomere length in aged fibroblasts, suggesting the compound may protect the genome from one of the most fundamental forms of wear and tear.

In addition, the treatment significantly increased levels of SIRT1, a gene that plays a central role in regulating cellular metabolism, DNA repair, and longevity. SIRT1 belongs to the sirtuin family of proteins, which have been widely studied for their anti-aging effects. Sirtuins help maintain genome stability and energy balance, and they often become less active with age. Psilocybin’s ability to upregulate SIRT1 provides another possible mechanism for its protective effects against cellular aging.

Improved Survival and Health Markers in Aged Mice

To test whether these cellular benefits might translate into whole-body effects, the researchers treated aged mice with psilocybin and tracked their survival. After several weeks of treatment, the survival rate of the psilocybin group reached 80%, compared to only 50% in vehicle-treated controls. The study did not report detailed physiological measurements, but researchers noted visible improvements in fur texture and pigmentation. Mice in the psilocybin group exhibited healthier coats and less white hair, suggesting that the treatment may also influence external signs of aging.

Although the precise mechanisms are still under investigation, the survival advantage suggests that psilocybin might influence more than one hallmark of aging. Aging researchers increasingly recognize that targeting a single pathway is often insufficient to achieve meaningful benefits. Instead, interventions that act on multiple interconnected aging processes—such as cellular senescence, telomere attrition, and epigenetic instability—are more likely to produce systemic improvements in healthspan.

Psilocybin and the Expanding Role of Psychedelics in Medicine

While psychedelics like psilocybin are primarily known for their neurological effects, research into their broader biological impact is rapidly accelerating. Several studies have shown that psychedelics may reduce inflammation, enhance neuroplasticity, and even promote regeneration in damaged tissues. These effects often occur at lower doses than those used to induce hallucinations, suggesting that psilocybin may have therapeutic properties even when taken in sub-perceptual quantities.

The potential link between psychedelics and anti-aging is especially compelling given recent evidence that mood, stress, and inflammation all contribute to accelerated aging. Chronic stress, for instance, has been shown to shorten telomeres and increase the production of senescent cells. If psilocybin can counteract these stress-related pathways—both directly and indirectly—it may offer a new route for slowing the biological clock.

Although human studies are needed to validate these findings, the current data suggest that low-dose psilocybin could one day be explored as a therapeutic for age-related conditions. By reducing the burden of senescent cells, boosting longevity genes, and preserving telomere length, this naturally derived compound opens new possibilities for slowing the aging process from the inside out.

Model: 19-month-old male C57BL/6J mice

Dosage: Daily intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 1 mg/kg psilocybin