Scientists Predict that Lifestyle Can Extend Lifespan by at Most One Year

Rather than lifestyle, substantially extending lifespan may involve reducing cellular damage and increasing damage removal, potentially with known longevity interventions.

Highlights

- According to an advanced mathematical model and real-world data, increasing the lifespan of humans involves reducing cellular damage and increasing damage removal.

- Possible interventions for achieving this include NAD+ precursors like NMN, mTOR inhibitors, and senolytics.

Piles of data from scientific research suggest that specific lifestyle interventions may extend lifespan and prevent chronic diseases. These lifestyle interventions include adequate sleep, a healthy diet, and regular exercise. However, a new study predicts that lifestyle can only extend lifespan by about a year, with the authors of the study saying,

“Our analysis predicts that lifestyle can extend maximal lifespan by at most ∼1 year…”

Modeling Lifespan

Life expectancy—the average number of years a person is expected to live (usually from birth)— has risen. Meanwhile, lifespan—the number of years a species can live— has remained largely unchanged, particularly for the last 150 years. This is despite scientists making incredible strides in extending the lifespan of other species, such as flies, worms, and mice.

Moreover, despite largely uncovering the molecular and cellular changes that occur with aging, scientists are still unsure of what precisely contributes to maximum lifespan. To address this, researchers from the Weizmann Institute utilized an advanced mathematical model that describes aging and mortality dynamics across species.

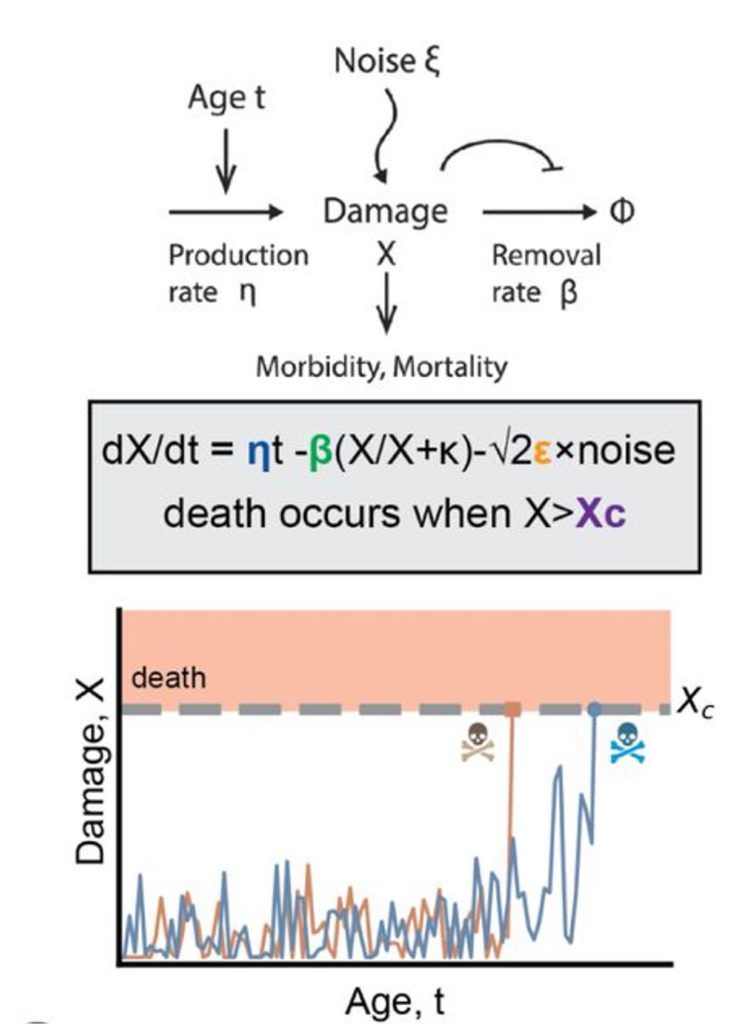

The model incorporates a causal form of damage, denoted as X, which accumulates with age. Death occurs when this damage reaches a threshold, denoted as Xc. According to the model, damage accumulation with age depends on the balance between damage production, η, and damage removal, β. The equation also incorporates random fluctuations in damage, ε.

When fitting their model to real-world data, the researchers found that altering either the damage production or the damage removal components led to unrealistic lifespan outcomes. In contrast, altering the maximal damage threshold or the random damage components led to more realistic changes in lifespan. The authors concluded that damage production and removal typically vary within a narrow range and do not significantly contribute to determining lifespan.

Longest-Lived Individuals

The lifespan of humans has increased since the mid-19th century, attributed to reductions in childhood mortality, sanitation, disease control, healthcare, and related external factors. After accounting for these external factors, the researchers determined that the maximal damage threshold and random damage components of their model fit well with historical data.

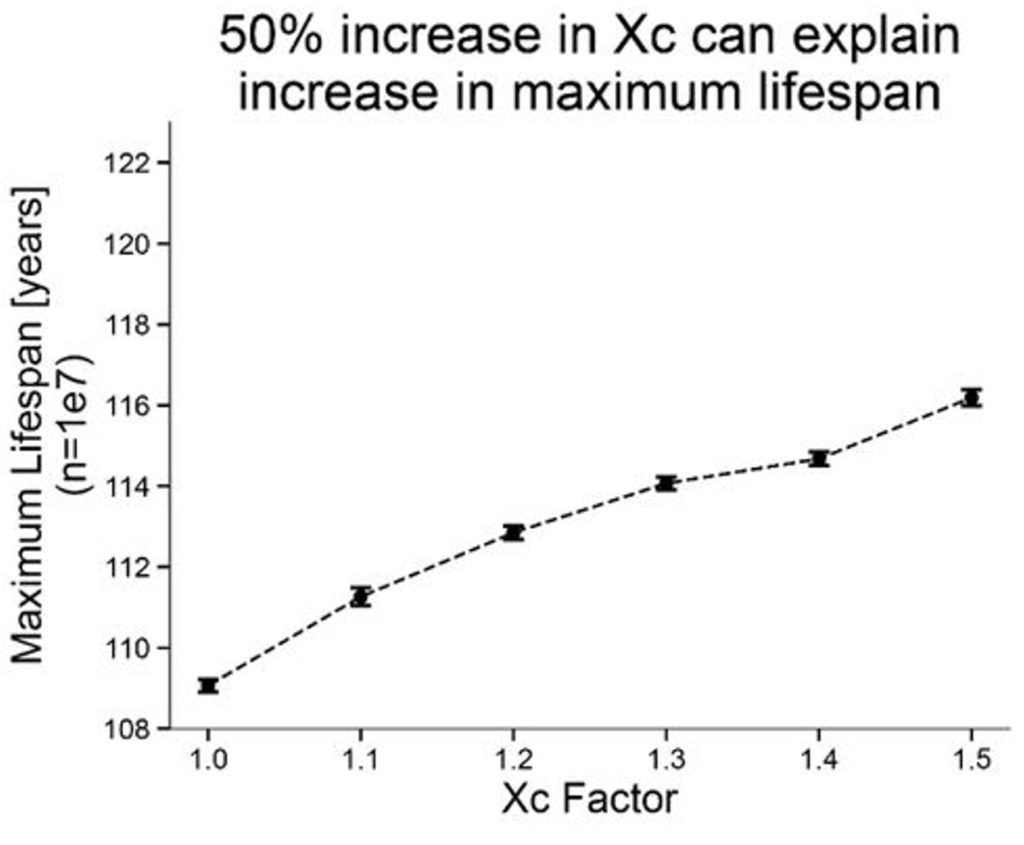

The researchers also examined the longest-lived people on record. The age of the oldest living person in 1960 was 109, while in 2020, the oldest person was 117. This modest increase in maximum lifespan could be explained by increasing the maximum damage threshold of the model by 50%. The authors say that such an increase reflects greater physiological robustness.

Genetics

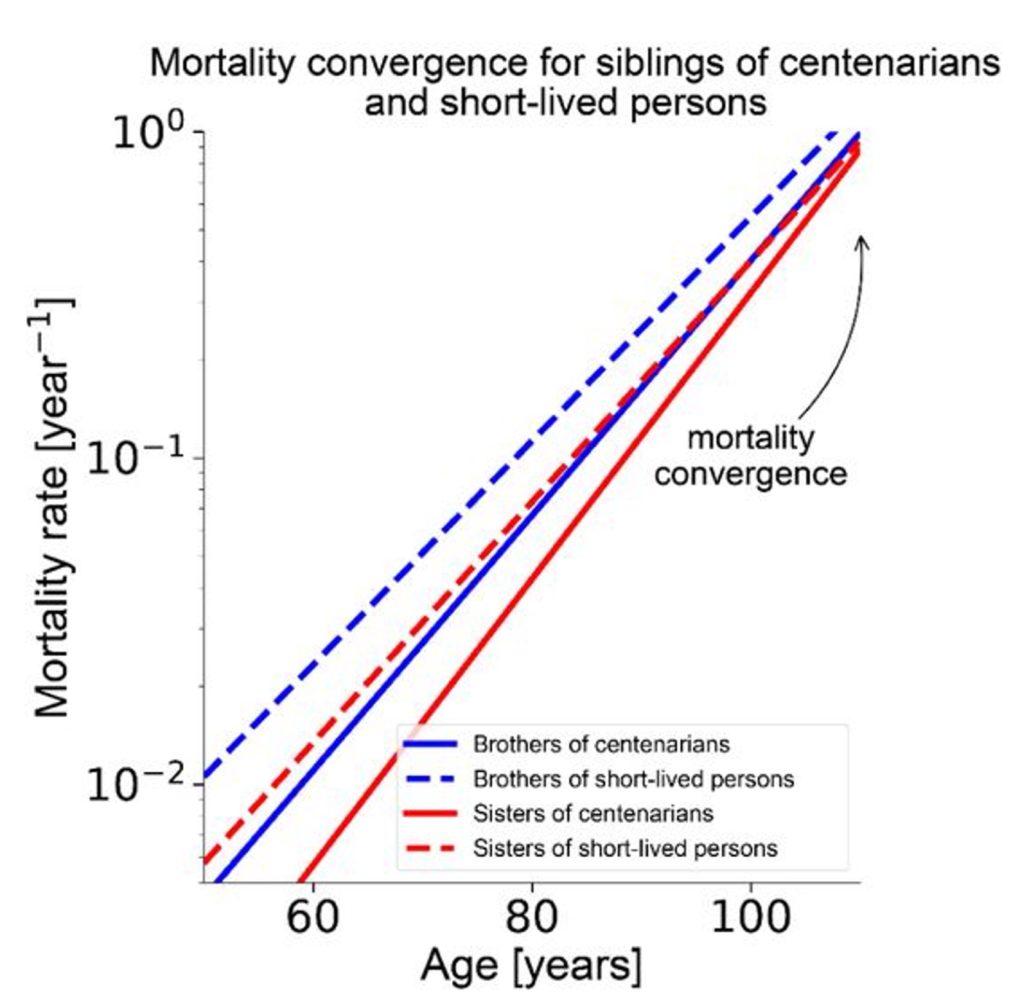

Long-lived individuals, such as centenarians (people who live to 100), often have siblings with similar favorable genetics, according to the Weizmann researchers. However, the siblings of centenarians exhibit mortality rates similar to short-lived persons (people who live to the age of 65). Since short-lived individuals likely have less favorable genetics, this convergence of mortality suggests that genetics does not play a large role in lifespan.

Using their mathematical model, the researchers found that the mortality convergence for siblings of centenarians and short-lived persons could be replicated by adjusting the maximal damage threshold or the random damage components of their equation. In contrast, adjusting damage production or damage removal failed to simulate the real-world data. Based on these findings, the researchers ruled out the role of genetics in determining maximum lifespan.

Lifestyle

Using real-world data, the researchers examined various lifestyle factors that have been shown to promote longevity, including:

- Good diet quality

- College education

- High income

- Physical activity

- Sleeping for 7 to 9 hours

- Weekly church attendance

These lifestyle factors contributed to a 1-5% increase in median lifespan—the age at which half the population being studied is still alive, and the other half has died. Again, the data fit well with an increase in damage threshold and a reduction in random damage, while changes in damage production and damage removal were ruled out.

Accelerated Aging

Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) is a rare genetic disorder that accelerates the aging process, whereby aging occurs about 6-fold faster. The researchers found that altering the maximal damage threshold or random damage components of their equation did not replicate the real-world data from HGPS patients. However, increasing damage production and reducing damage removal recapitulated the data. These findings suggest that increasing damage and lowering damage removal can accelerate the aging process.

Interventions that May Increase Lifespan

According to their model, the authors of the study concluded that lifespan gains are primarily driven by a higher damage threshold (Xc) and lower random damage (ε). The factors driving the higher damage threshold include improved medical care, infection resistance, and reduced vulnerability to diseases. The random damage “represents short-term physiological fluctuations (circadian rhythm, stress, immune variability). This explains why lifestyle predominantly affects Xc and ε, extending median but not maximal lifespan.”

The Role of Senescent Cells

The Weizmann researchers interpret damage, X, as the burden of damaged or inflammatory cells, including senescent cells. Senescent cells are those inflammatory cells that accumulate with age. In their equation, damage production (η) reflects the accumulation of “error factories,” which may include senescent cells. Senescent cells are usually removed by the immune system, but are thought to accumulate due to age-related impairments in immune function. Along those lines, the researchers interpret damage removal (β) to include the immune system’s clearance of senescent cells.

Interventions that May Increase Lifespan

The researchers suggest that reducing damage production and increasing damage removal may extend maximal human lifespan. When it comes to senescent cells, this would involve preventing the cellular stressors that trigger senescence, such as interventions that target mTOR and mitochondria. Clearing out senescent cells, which would equate to increasing damage removal, could be achieved with senolytcs.

The most notable intervention that targets mTOR is rapamycin, an FDA-approved drug that inhibits mTOR and has repeatedly been shown to extend the lifespan of animals. When it comes to mitochondria, NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) precursors are known to improve mitochondrial health by raising NAD+ levels in animal studies. NAD+ precursors include NMN (nicotinamide mononucleotide) and NR (nicotinamide riboside). Senolytics, such as fisetin and quercetin, are compounds that remove senescent cells.

While not mentioned by the researchers, combining mTOR inhibition, NAD+ restoration, and senescent cell removal may lead to synergistic effects. This concept was previously understood by Seragon scientists, who developed Restorin. Restorin targets mTOR, mitochondria, and senescent cells, aiming to slow or prevent cellular damage and promote health and longevity. Still, more research is needed to confirm whether targeting these cellular drivers of aging is advantageous for healthy older adults.