Scottish Scientists Determine How Much Food to Eat for Prolonging Lifespan

Caloric restriction — reducing food intake without malnourishment — significantly increases mouse survival rates only when calories are reduced by 40% while reducing calories by 20%, or 30% shows modest benefits.

Highlights:

- A caloric deficit of 20%, 30%, or 40% increasingly raises survival rates, attributed largely to slowing the progression of cancer.

- On average, a calorically restricted diet leads to the stabilization of body weight after 30 days.

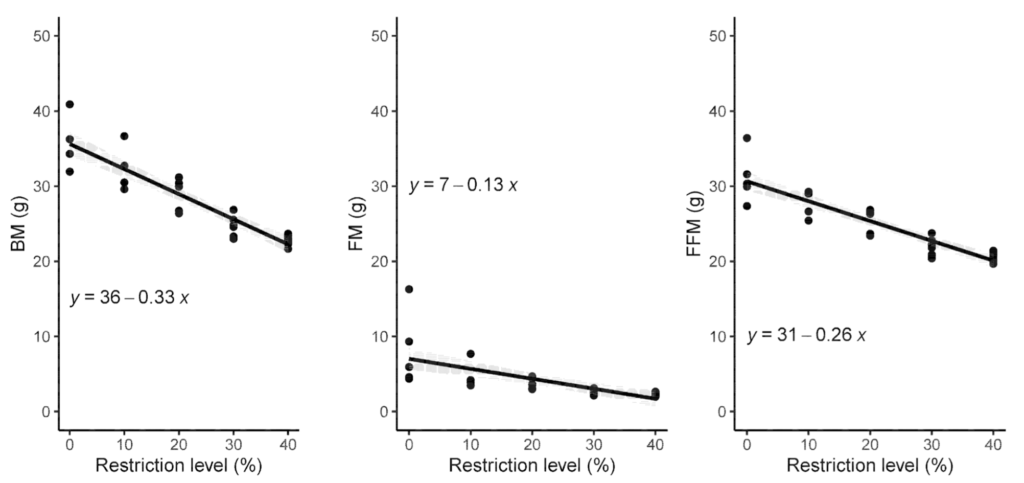

- Losses in fat and fat-free mass (muscle, bone, & other organs) increase as calories are reduced.

From yeast to mice, the most reliable method for extending lifespan is caloric restriction (CR). However, the benefits of CR may not apply to everyone, as CR shortens the lifespan of some mouse strains. Therefore, the details of how to approach a personalized CR regimen remain unclear. This includes just how much of a caloric deficit is necessary for promoting longevity.

Now, researchers from the University of Aberdeen in Scotland may have found the answer. As reported in The Journal of Gerontology, Mitchell and colleagues explore the effects of different levels of CR on lifespan and body composition in mice. They find that a 40% caloric deficit significantly increases survival, while lower deficits only modestly increase survival. Furthermore, it is confirmed that there is a direct correlation between weight loss and calorie intake reductions.

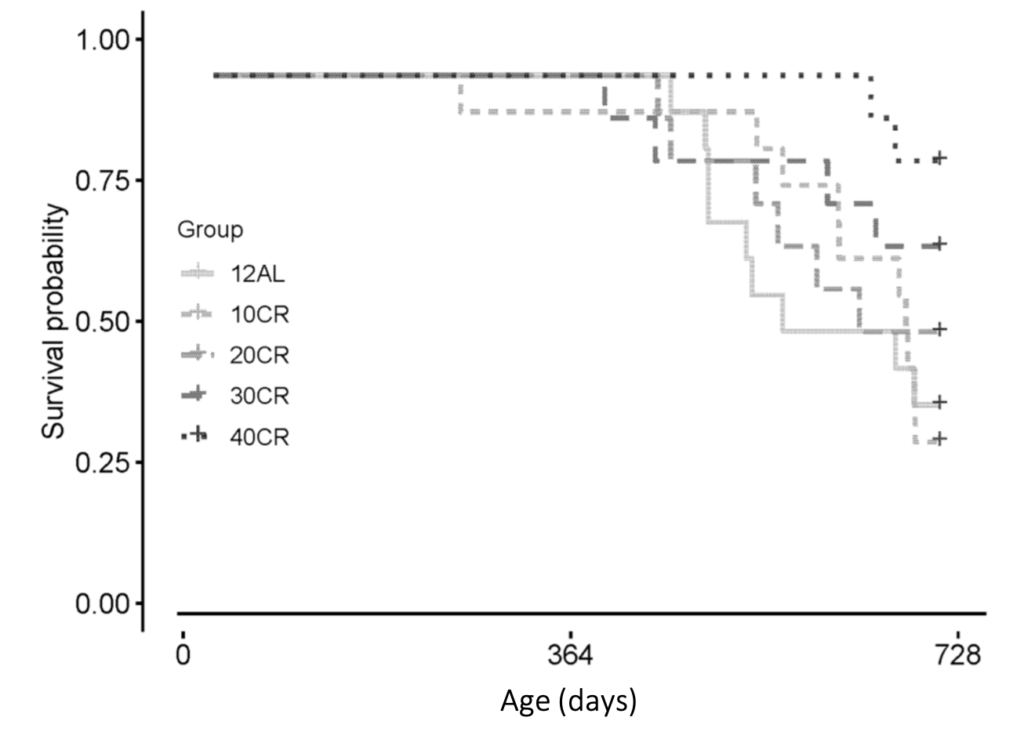

A 40%, but not 10%, 20%, or 30% Caloric Deficit Significantly Increases the Survival Rate of Mice

To develop a better understanding of how CR affects longevity, Mitchell and colleagues placed mice into four groups with different levels of CR: 10% deficit (10CR), 20% deficit (20CR), 30% deficit (30CR), and 40% deficit (40CR). The four groups of CR mice were compared to mice with free access to food for 12 hours of the day (12AL). CR was initiated when the mice were 5 months old and continued until they were 24 months old. This is the human equivalent of starting CR at 20 years old and continuing until 70 years old.

A total of 33 out of 64 mice remained alive over the 19-month CR intervention. Compared to 12AL mice, only the 40CR mice showed a statistically significant improvement in survival with a 47.6% increase. In contrast, the 20CR mice had a 14.3% increase and the 30CR mice had a 31% increase, but these increases were not statistically significant. Furthermore, the 10CR mice had a lower survival rate than the 12AL mice, but this also was not statistically significant.

The researchers next determined the assumed cause of death for the mice via autopsy. They concluded that the primary cause of death was cancer, of which liver cancer was the most common. Moreover, cancer incidence was the lowest in the 40CR mice, suggesting that CR slows the progression of cancer.

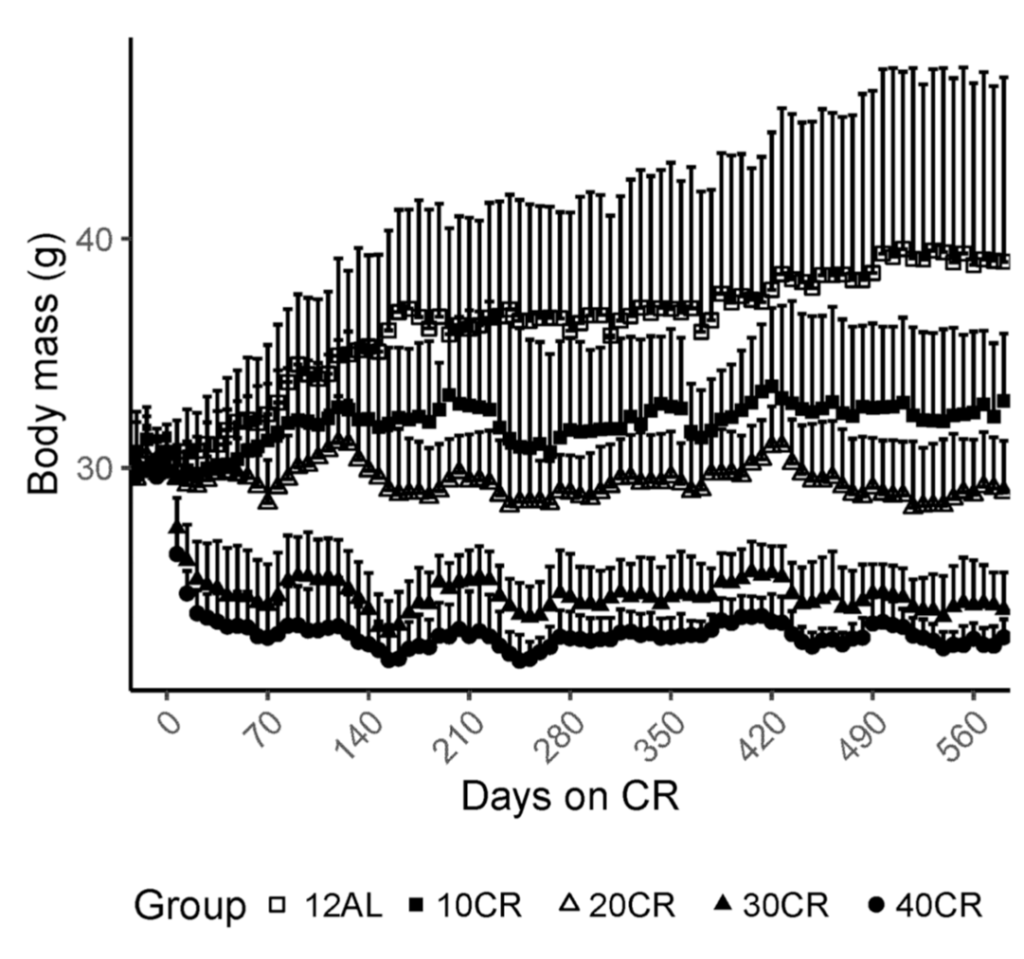

While the mice were alive, Mitchell and colleagues took body weight measurements over the course of the CR intervention. They found that, on average, the body mass of the mice stabilized after about 30 days. This was attributed to the loss of both fat mass and muscle mass, whereby stabilization occurred once muscle mass was sufficiently reduced to generate less energy demand. These findings suggest that the weight loss benefits of CR may plateau after about 30 days.

“Here we reveal that the key changes in body composition occur in the first 30 days and is maintained thereafter with tight daily regulatory control,” say the authors.

Since weight loss can occur due to fat loss and muscle loss, Mitchell and colleagues used dual energy x-ray absorptiometry analysis (DXA) to measure body composition. They found that the observed weight loss of the mice was mostly due to fat loss. However, fat-free mass, which includes the mass of muscle, bone, and other organs, also decreased. As expected, there was a direct relationship between CR level and mass loss, with higher CR levels correlating with higher body mass, fat mass, and fat-free mass losses.

Is Caloric Restriction a Good Idea for Humans?

Beyond weight loss, forms of CR like fasting from dawn to sunset have been shown to lower blood pressure and mitigate insulin resistance in obese individuals. In healthy and obese individuals, restricting calories by 14% for two years has been shown to reduce inflammation by preventing the shrinkage of the thymus, an immune system organ. In normal weight and slightly overweight individuals, reducing calories by 25% for two years has been shown to lower mortality risk and slow the pace of biological aging.

These findings suggest that CR is beneficial to humans and that a 40% caloric deficit isn’t necessary for these benefits. However, it is possible that a caloric deficit of 40% is necessary to significantly prolong lifespan. Assuming a caloric intake of 2,500 calories, which is recommended for males, a 40% caloric deficit would be about 1,500 calories. While still maintaining a heart-healthy diet, a 1,500 calorie meal plan would look like this:

Breakfast: 2 large eggs, 2 slices of whole grain bread, peanut butter.

Lunch: 2 slices of whole grain bread, 1 can of tuna, 1 slice of low-fat mozzarella cheese, 1 tablespoon of a fat or oil product like mayonnaise, 1 cup of skim milk, 6 baby carrots, 1 tablespoon of light dressing.

Dinner: 4 ounces of grilled chicken, 1 cup of sweet potatoes, 1 cup of green beans, half a tablespoon of olive oil, 1 medium apple, and 1 cheese stick.

Snacks: Half a cup of pineapple, half a cup of cottage cheese.

Model: Male C57BL/6J mice

Intervention: 40% caloric deficit