The Inflammation Myth: New Insights on Aging

Columbia University scientists find that inflammation increases the risk of common chronic age-related diseases only in people from industrialized populations.

Highlights

- Individuals from non-industrialized populations (i.e., the Orang Asli and Tsimane) do not show age-related increases in inflammation like their counterparts from industrialized nations (i.e., Italy and Singapore).

- Non-industrialized populations also do not show an increased risk for age-related diseases associated with inflammation.

- We note ways of mitigating the potential age-accelerating effects of modern living.

Science can be overly dogmatic, and the science of aging is no different. Within the field of aging biology, a concept has gained traction: as we age, our bodies are increasingly affected by low-grade inflammation, which can lead to chronic age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and certain types of cancer. It’s a compelling idea, but what if it’s not the whole story?

What if modern living is to blame? A new study in Nature Aging suggests that inflammation may not be an inevitable consequence of aging. A team of researchers, including those from Columbia University in New York, discovered that this inflammatory signature of aging is virtually absent in some populations, particularly those detached from the industrialized world.

Examining Two Worlds

The international research team, including researchers from the United States, Singapore, France, and Russia, compared four distinct populations:

- The InCHIANTI cohort, consisting of individuals from the Chianti region of Italy

- Participants from the Singapore Longitudinal Aging Study (SLAS)

- The Orang Asli, the indigenous peoples of Peninsular Malaysia

- The Tsimane, the indigenous peoples of the Bolivian Amazon

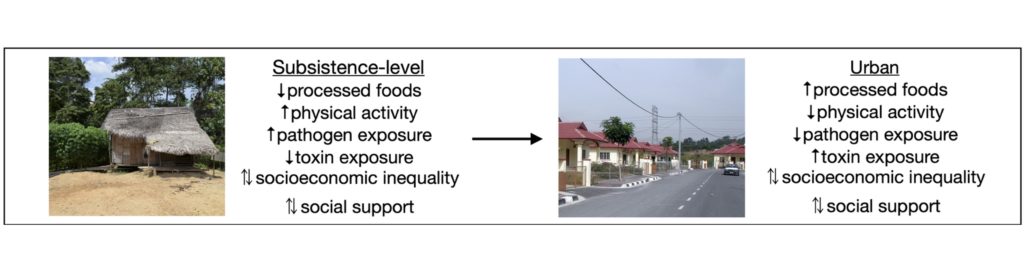

The groups from Italy and Singapore represent industrialized societies, with modern diets, sanitation, and healthcare. The Orang Asli and Tsimane live in environments more similar to those of our ancestors, with high exposure to pathogens, physically demanding lifestyles, and locally sourced diets.

Inflammaging

Over decades of researching individuals from industrialized nations, scientists have noticed that body-wide chronic inflammation increases with age. Chronic inflammation has been found to contribute to the deterioration of nearly every organ system, making it an underlying factor in virtually every chronic age-related disease. In turn, scientists have established a framework for this phenomenon that attempts to explain the aging process itself, calling it “inflammaging.”

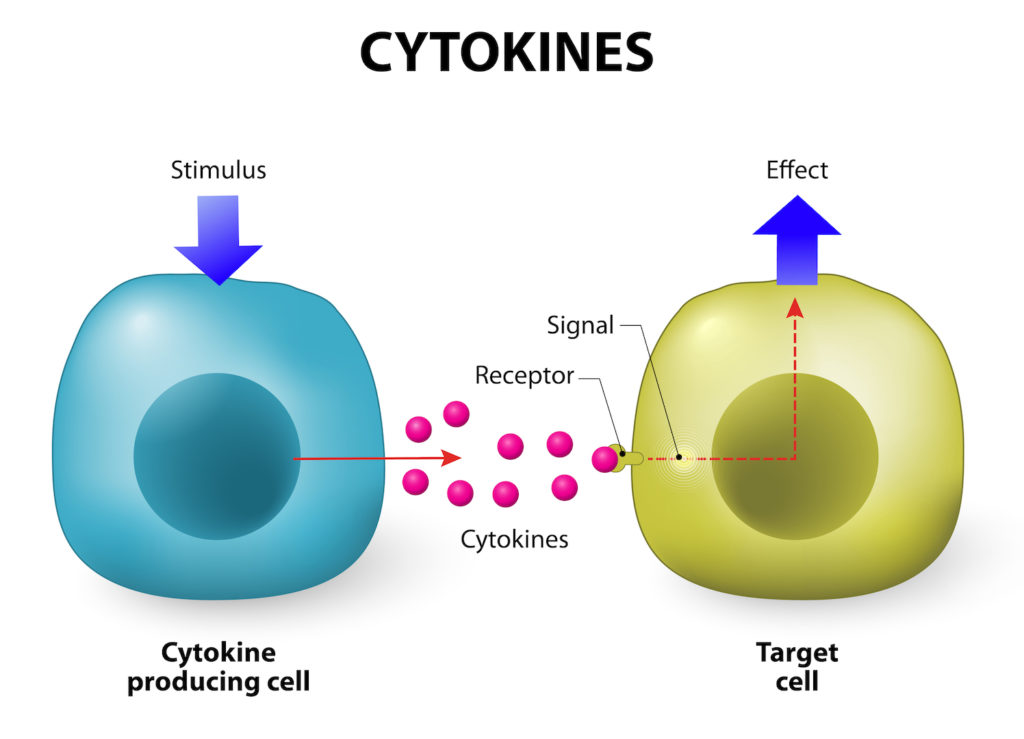

However, scientists have yet to decide upon how to precisely measure inflammaging. In one respect, inflammation can be assessed by measuring signaling proteins called cytokines. Nevertheless, this assessment comes with limitations, as there are many cytokines, some of which can be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory, depending on the circumstance. This can make it difficult to choose a panel of cytokines that can reliably assess an individual’s inflammaging status.

With limitations in mind, the international research team devised a method for measuring inflammaging based on the variability of cytokines. They ultimately found that populations from non-industrialized cultures show little cytokine variability amongst members when compared to populations from industrialized nations.

Inflammaging Increases Only in Industrialized Populations

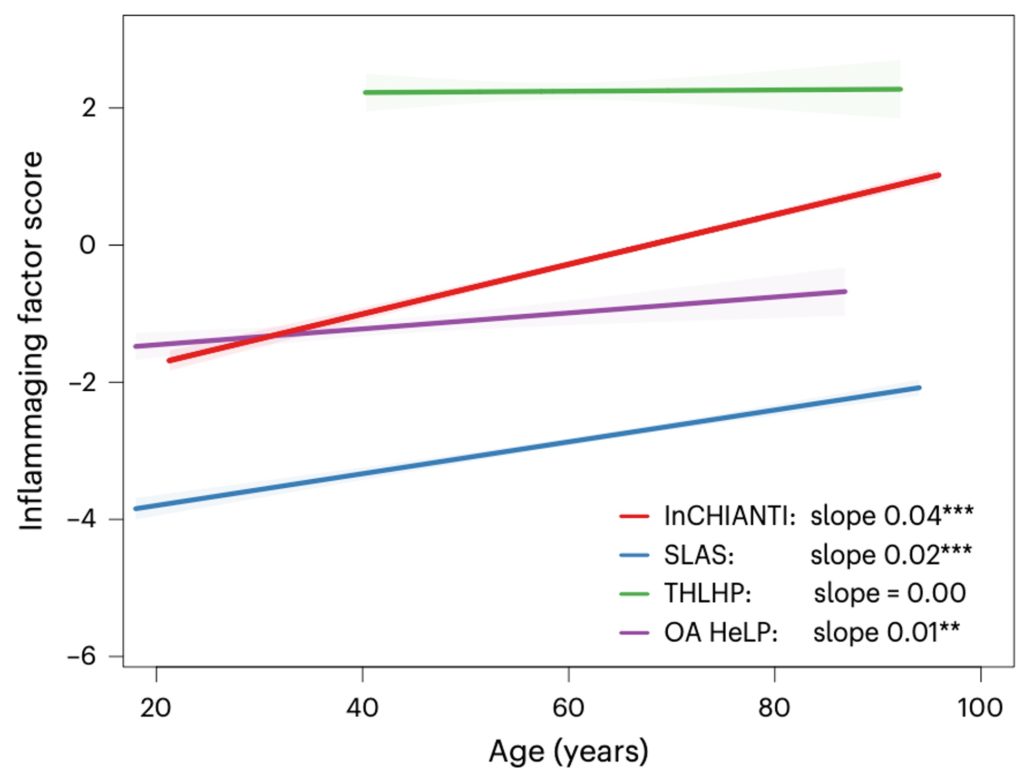

To compare the inflammaging status of different populations, the researchers employed a previously examined reference population: the InCHIANTI cohort. A previous study of the InCHIANTI cohort showed a strong correlation between elevated levels of 19 cytokines and age. Moreover, these 19 cytokines were able to predict the mortality rates of individuals from the InCHIANTI cohort. Thus, the 19-cytokine panel was validated as a measure of inflammaging, at least in this industrialized population.

The 19 cytokines measured from the InCHIANTI cohort were used as a reference for comparison to the other populations. However, not all 19 cytokines were measured from each of the populations examined. For the SLAS population, 16 of the same cytokines were measured, and for the Orang Asli and Tsimane populations, 8 of the same cytokines were measured. Still, these cytokine measurements were used to generate an inflammaging factor score. Based on this score, it was found that inflammaging increases in the industrialized InCHIANTI and SLAS populations, but not the non-industrialized Orang Asli and Tsimane populations.

Inflammaging Increases Risks of Age-Related Diseases in Industrialized Populations

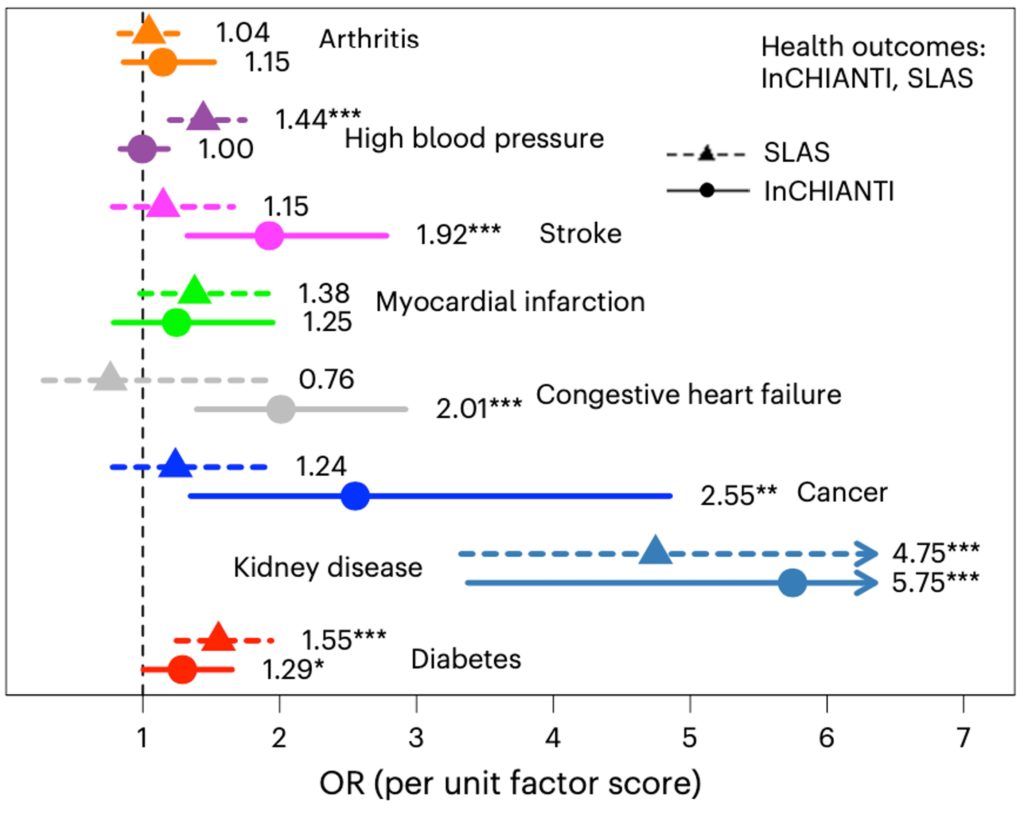

The determine how inflammaging may contribute to manifestations of aging, the researchers made associations between inflammaging scores and chronic age-related diseases. In the SLAS population, they found that elevated inflammaging was associated with high blood pressure, kidney disease, and diabetes. In the InCHIANTI population, inflammaging was associated with stroke, congestive heart failure, cancer, and kidney disease. In stark contrast, inflammaging was not associated with any chronic age-related diseases in the Orang Asli or Tsimane populations.

Together, these findings suggest that individuals from industrialized nations like Italy and Singapore are at higher risk for age-related chronic diseases associated with inflammaging. This differs markedly from populations detached from industrialized society, such as the Orang Asli and Tsimane, who show no significant age-dependent increase in inflammation associated with age-related disease rates.

Does Modern Living Trigger Disease in Older Age?

The study suggests that inflammaging is not a universal biological law of human aging, or a so-called hallmark of aging. Instead, it appears to be a byproduct of an industrialized lifestyle. As the study’s authors note, this work is part of a broader trend of “questioning the generalizability of health-related findings from high-income populations.”

The Evolutionary Mismatch Theory of Aging

The researchers propose that their results may be explained by the evolutionary mismatch framework, which states that our immune systems coevolved with our lifestyle and environment. However, evolution works over thousands of years, while the rapid industrialization of our society began only a few hundred years ago. Thus, according to the framework, this has led to a mismatch between our immune systems and the environment and lifestyle we are born into.

The international team of researchers also points out that many of the Orang Asli and Tsimane are exposed to infections, leading to major differences in cytokine profiles.

“Indeed, much cytokine variation in these populations is probably due to the type and severity of current infections, not aging. Roughly 66% of Tsimane have at least one intestinal parasitic infection: 30–40% of adults present with a gastrointestinal infection, 20–30% have a respiratory infection, 25% leukocytosis and 86% eosinophilia. In the Orang Asli, 70% have a prevalent infection: 27% respiratory, 22% fungal, 30% leukocytosis and 41% eosinophilia. Additionally, helminths, which are common among the Tsimane and Orang Asli, may have protective effects,” they say.

Mitigating Disease in Industrialized Nations

The evolutionary mismatch theory of aging raises of few questions about modern society. Modern advances in hygiene, sanitation, and vaccines have greatly reduced mortality rates from infectious diseases, but what consequences do these advances have on our immune system? Moreover, are there steps that can be taken by industrialized populations to mitigate age-related diseases that are apparently related to modern society?

Luckily, the answer to the second question seems to be yes. To reduce the risk of age-related diseases, including heart disease (the number one cause of death), one can limit the consumption of processed foods and partake in regular physical activity. These simple actions, if applied correctly, may potentially mean the difference between life and death. Additionally, another critical factor could be psychosocial stress induced by the modern-day lifestyle. This can be mitigated in several ways, including exercise and a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, nuts, and fish.