The Secret to Delaying Aging and Treating Chronic Stress: New Theory

Preserving mitochondrial health may be the key to preventing cellular aging, and scientists reveal tactics for doing so, according to their new theory.

Highlights

- Stress allocates the cellular energy produced by mitochondria to processes that are not conducive to aging normally.

- Cultivating the activation of the parasympathetic nervous system allows energy to be expended on restorative cellular processes that counteract aging.

“We must continuously breathe precisely to bring oxygen to mitochondria…” — Cromwell and colleagues.

Mitochondria—the cellular organs that utilize oxygen to produce life-sustaining energy—are the reason we breathe. It is becoming more apparent that mitochondria not only play a key role in the aging process but may be the root cause of aging itself. Mitochondria are also tied to stress-related diseases, providing a tangible link between psychological stress and premature aging.

The Energetic Costs of Stress

Stress is characterized by the detection of a perceived threat, which is followed by a physiological cascade of cellular events that prioritizes survival. These events include the release of powerful hormones like cortisol and adrenaline, which elevate blood pressure and heart rate. Stress also triggers the release of signaling molecules known as cytokines.

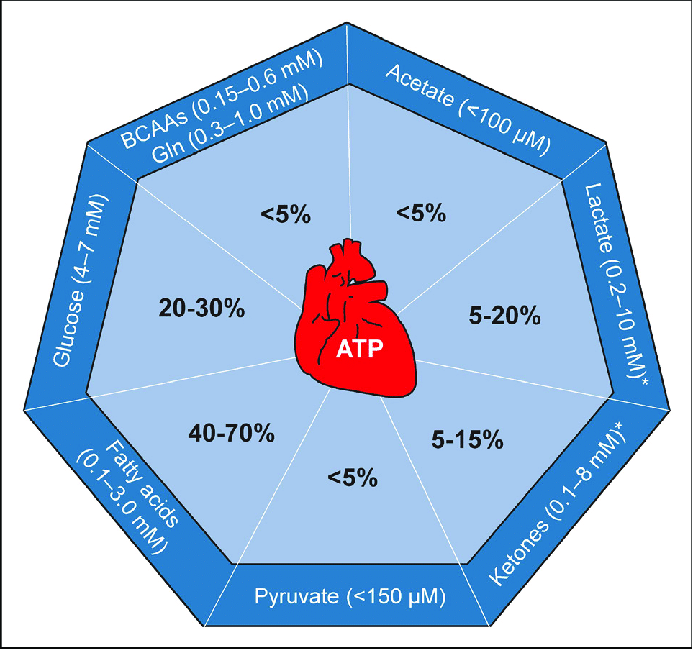

Hormones and cytokines are proteins synthesized by our cells. Protein synthesis is one of the most energetically costly cellular processes, requiring enormous amounts of ATP (adenosine triphosphate)—the cellular energy currency produced by our mitochondria. Moreover, each heartbeat requires ATP, so the increase in heart rate provoked by stress is also energetically costly.

The Energy Necessary to Protect Against Aging

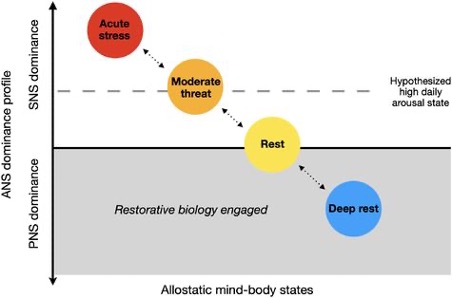

As part of their recently published theory, scientists from the University of California, San Francisco, Columbia University, and the University of Denver propose that energy allocated to stress subtracts from the energy otherwise spent on counteracting aging. Namely, threat arousal—stress—is an energetic state that prioritizes survival and preparation over optimization.

- Surviving: In survival mode, our cells use ATP to repair acute damage and maintain the physical integrity of the processes necessary to respond to acute threats.

- Preparing: Once basic survival needs have been met, ATP can be used for predictive regulation (allostasis)—preparing for upcoming demands, such as new threats.

- Optimizing: Once there are no threats to take care of or plan for, ATP can be used for cellular restoration.

How Cellular Restoration Counteracts Aging

Cellular aging concerns the accumulation of molecular damage that leads to disruptions in organ function and eventually death. Cellular restoration involves the processes that counteract cellular damage, thereby mitigating organ dysfunction and delaying death. Mitochondria are a core component of cellular restoration, as they are the primary producer of ATP, which fuels all cellular processes, including restorative processes. Stress taxes our mitochondria, making them unhealthy and more likely to trigger cellular damage.

Cultivating Parasympathetic Dominance

The most empirically supported method for lowering threat arousal is by modulating the autonomic nervous system (ANS)— the part of the nervous system that controls involuntary bodily functions, such as blood pressure, heart rate, and digestion. The ANS is subdivided into two, often opposing, branches:

- Sympathetic nervous system (SNS): The “fight or flight” system that mobilizes energy. By releasing hormones like adrenaline, energy in the form of glucose and fat is mobilized, increasing blood glucose and fat levels.

- Parasympathetic nervous system (PNS): The “rest and digest” system that conserves energy. It promotes calm, recovery, and maintenance, a state optimal for cellular restoration.

Similar to our five senses, our breathing rate communicates the status of our environment to our brain. Our breathing rate signals whether we are in the presence of a threat or if we are safe from threats. Slowed breathing can cultivate parasympathetic dominance, signaling “safety” to the brain. This activates the vagus nerve, the primary nerve of the PNS that relays information concerning oxygen availability.

Additionally, breathing more slowly and deeply generally improves oxygen utilization by our mitochondria, improving their health and efficiency. Breathing at a rate of about six breaths per minute has been linked to positive health outcomes. Slow breathing, also called vagal breathing, has also been shown to lower heart rate variability and blood pressure. Contemplative practices, such as meditation and prayer, are known to slow breathing and lead to positive health outcomes as well. There are also devices available that can activate the vagus nerve, as we have reported previously.

Practice Makes Perfect

The effects of slow breathing can be felt nearly instantaneously, particularly in people who normally exhibit shallow and fast breathing. Still, studies suggest that daily contemplative practice, which usually involves slowed breathing, leads to parasympathetic dominance. In other words, practicing slow breathing can lead to lasting changes to the nervous system that reduce susceptibility to stress and premature aging.

Thoughts and Perceived Threats

Certain thoughts can be perceived as threats and activate the SNS, leading to stress and accelerated aging. Cultivating parasympathetic dominance entails reducing the activation of the SNS to reduce the physiologically harmful effects of psychological stress.

Breathing slowly can help to identify thoughts that would normally trigger acute or moderate stress states. A common thought pattern that induces stress is worry, particularly the repetitive, unhelpful dwelling on negative thoughts pertaining to the past or future. This form of worry (not thinking about the present) is unproductive and promotes accelerated aging by increasing sympathetic dominance.

The identification and cessation of worry-related and other negative thoughts can cultivate parasympathetic dominance. Supporting this notion, an analysis of 135 studies found that emotional regulation, including negative affect regulation, was associated with higher cardiac vagal control—activating the vagus nerve to control heart rate and heart rate variability—which indicates greater resting parasympathetic dominance.

Preventing Premature Aging

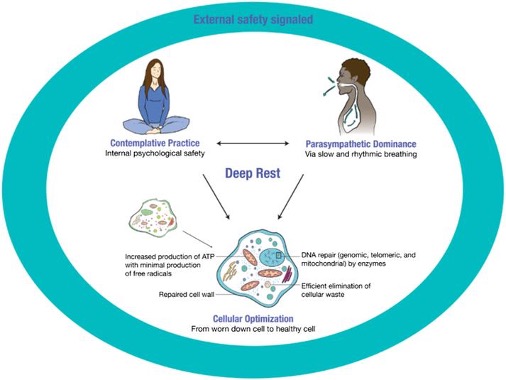

Contemplative practices and parasympathetic dominance help us to enter a state of deep rest. In this state, our cells can allocate ATP to restorative processes that counteract cellular aging. Practicing contemplation and parasympathetic dominance can cultivate a mind free of negative thoughts that are perceived as threats and trigger stress.

By allowing our cells to restore themselves, we can potentially prevent, at least temporarily, the cellular aging process. In contrast, being in a constant state of stress reduces cellular restoration, thereby promoting cellular aging. It follows that the more stressed we are, the more likely we are to age prematurely at the biological level.

6 breaths per minute: Count to six while inhaling through the nose, then count to six while exhaling through the nose. Repeat.