Plant-Based Senolytic Flavonoids Are Linked to Slower Aging: New Study

Researchers link adults who consume high levels of dietary flavonoids with lower whole body, heart, and liver biological age — one’s age-based physiological status compared to others in the same age group — compared to their chronological age in years.

Highlights

- High flavonoid content diets for those who don’t smoke or drink high levels of alcohol tend to confer lower blood marker-based biological age readings compared to chronological age: -1.10 years for the whole body, -1.68 years for the heart, and -4.69 years for the liver.

- A high flavonoid diet is more likely to slow aging in adults who are 60 years old or older, don’t smoke, mildly consume alcohol, and exercise.

Flavonoids are derived from plants and are abundant in fruits and vegetables contained within the Mediterranean diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, fish, and olive oil. Flavonoids possess antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity, and interestingly, the senolytics fisetin and quercetin, which selectively kill non-proliferative senescent cells that emit inflammatory molecules, are flavonoids. Although researchers have presumed that flavonoids counter aging, no study had confronted whether they’re actually linked to decelerated aging, until now.

Published in the Journal of Translational Medicine, Chen and colleagues from Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Geriatrics in China show that dietary consumption of high flavonoid levels are tied to whole body, heart, and liver biological ages that are less than study participant chronological ages. Study participants most likely to benefit from flavonoid enriched diets were 60 years old or over, didn’t smoke, mildly consumed alcohol, and exercised. The study’s findings provide the first assessment showing that high flavonoid intake decelerates aging as shown by lower biological ages compared to chronological ages.

A Flavonoid Enriched Diet Decelerates Aging, Especially in Those Aged 60 Years and Older

Chen and colleagues used a blood chemistry based method to assess biological age in 3,193 adult participants who were divided into three groups based on the level of their dietary flavonoid consumption. The researchers found that in adults who consumed the highest flavonoid levels but who didn’t smoke or excessively consume alcohol, biological age readings were 1.10 years less than chronological age for the whole body, 1.68 years less for the heart, and 4.69 years less for the liver. These results confirm what researchers had suspected — that a diet rich in flavonoids decelerates aging such that whole body, heart, and liver biological ages were significantly lower than participant chronological ages in years.

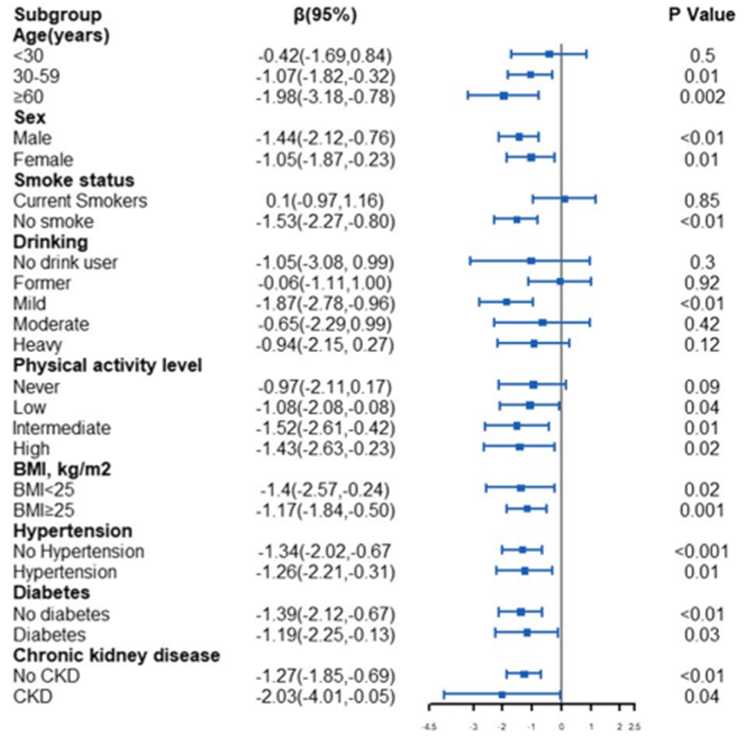

Chen and colleagues sought to find what factors and habits may contribute to flavonoid-enriched dietary benefits against aging. They compared participant age groups, smoking and drinking habits, along with whether they exercised. The researchers found that a high-flavonoid diet contributed to lower biological ages compared to chronological ages when the participants were 60 years old and over, didn’t smoke, mildly consumed alcohol, and practiced some sort of exercise regimen. These findings suggest that older individuals benefit more from flavonoid consumption, especially when they don’t smoke, don’t excessively consume alcohol, and get some form of exercise.

“This is the first population-based study to investigate the link between flavonoids intake and whole body and organic biological aging using a blood-based biomarker for biological age,” said Chen and colleagues. “It is possible that diets rich in flavonoids may be beneficial in delaying aging and promoting overall health.”

Utilizing More Sophisticated Biological Age Assessments to Confirm Flavonoids’ Anti-Aging Benefits

The study’s limitations include that it only included aging markers present in blood, however, there are other ways to gauge aging based on the lengths of chromosome ends (telomeres) along with DNA markers called methyl groups (methylation), among others. As such, it’s uncertain how accurate the biological age readings were compared to other, possibly more advanced, biological age assessments. Another limitation was that the potential for the interference of medication usage on readings of blood markers for aging wasn’t considered. Since more people aged 60 and over use medications, this may have had something to do with why this age group showed the best results for high dietary flavonoids. Moreover, this was a correlational study measuring ties between biological age and high flavonoid consumption, which doesn’t infer causation. Future research should find a way to eliminate the effects of medication use and employ other methods of biological age evaluation to confirm that high dietary flavonoid consumption decelerates aging. Future research should also investigate mechanisms behind how consuming high levels of flavonoids can slow aging to show some sort of causative effect.

Model: Adults with an average age of 47.62 years

Dosage: Average of 15.09 mg/day of flavonoids for tertile one; average of 51.96 mg/day of flavonoids for tertile two; average of 449.27 mg/day of flavonoids for tertile three